Now in Perspectives: Teaching and Researching with Empathy and Imagination

As I was preparing the October issue of Perspectives on History for the printer, I read with great interest a blog post by L.D. Burnett on “the weight.” Writing about a woman discovered only through her marginal notes in a text and a few scattered facts from a Google search, Burnett described why knowing more would be unwelcome: “I don’t want to know, because I don’t want to care. Not because I lack empathy, but because as a historian and as a person I suffer from a surfeit of it.”

A few weeks earlier, I’d read a post at The Junto by Michael Blaakman, “Historians Who Love Just a Bit,” on his growing fascination with a research subject, and “The enemies of analysis: enmity and adoration. What do you do when you feel both?”

Both of these posts resonated because I was working on a set of four articles, which appear in the October issue of Perspectives on History, that all arrived at around the same time and happened to ask related questions. What do we do with historical empathy? Of what value is the inevitable feeling of human connection between historian and subject? What about historical treatments of living subjects? And how can we teach historical imagination without leading students to believe that history is just a playground of fictionalizations?

A draft of an article by Heather Ann Thompson, on the perils of the recent past, and a teaching article by Kathryn Ciancia and Edith Sheffer on using fictional characters in the history classroom got me started, and I added articles from Keith David Watenpaugh and Mark Carnes. Watenpaugh wrote about how historical empathy can be turned into a tool of analysis. It is not merely something that gets in the way. And Mark Carnes discussed how Reacting to the Past games allow a connection to the past while demonstrating how elusive and contested the past can be.

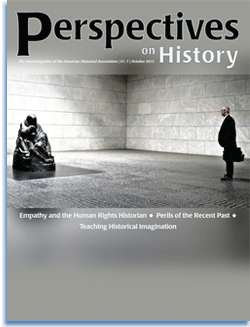

There’s nothing more satisfying for an editor than watching such things come together. Even the cover photograph I found seemed to speak to these issues: A visitor to a memorial cautiously regards a sculpture that originated as an intensely personal statement, but now stands in for all those who have suffered in war and at the hands of tyrants. The visitor is reticent, unsure of the emotions that the sculpture, of a woman holding her dead son, might provoke. Should historians connect, on this human level, to the past? To what extent? And how much of that should enter our work?

There’s nothing more satisfying for an editor than watching such things come together. Even the cover photograph I found seemed to speak to these issues: A visitor to a memorial cautiously regards a sculpture that originated as an intensely personal statement, but now stands in for all those who have suffered in war and at the hands of tyrants. The visitor is reticent, unsure of the emotions that the sculpture, of a woman holding her dead son, might provoke. Should historians connect, on this human level, to the past? To what extent? And how much of that should enter our work?

I’m curious what Perspectives readers think of these four articles when considered together (my own very modest contribution is at the back of the issue). The pitfalls of embracing an empathic approach to the past are enormous, as pointed out by Burnett and Blaakman. The articles in the October Perspectives point to possible benefits, and also to how hard it is to avoid empathy all together. We’d love to hear from you. Please leave your comments in the discussion section of each article, or in the Perspectives section of AHA Communities.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Activities AHA Today Thematic Teaching & Learning

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.