As graduate student coordinator of Columbia’s History in Action (HIA) program, I recently sat down with Mookie Kideckel, Alma Igra, and Jordan Katz, who received project funding through HIA to put history into action through their research on food history. Alma and Jordan write at Leftovers (recently highlighted at TIME History!), where they recreate historical recipes and post other tidbits about food in the past. Mookie is creating an app-based walking tour of food sites on the Lower East Side for the Museum of Food and Drink. What follows is part of the conversation we had about food and the connections between these projects and these historians’ other academic work.

“Jordan and Alma often get other historians involved in the process of going from ancient text into food. Mallory Ditchey translated and provided commentary on Tablet YBC 4644 from the Yale Babylonian Collection for this post on Mesopotamian beet broth.” (Mallory Ditchey, Yale Babylonian Collection, Mesopotamian beet broth) Credit: Avner Barak.

Jake Purcell: So, a simple question to start: Why food?

Alma Igra: I’ve been writing about food and developing recipes for many years before grad school. I’ve also found food history is very immediate to students—food is related to culture and memory, to the differences between cultures, to poverty, and to perceptions of the welfare state.

Jordan Katz: Here in Vermont there is a huge local food culture of people who hope to change the world through food, with this philosophy of, “we change the way we eat, we change the way we live.” I think there’s truth to that, but I also think that if we change the way we think about food, we change the way we think about history.

Mookie Kideckel: I’m interested in food as a vessel for social ideas. Eating is a proxy for pleasure, health, ability to do work, etc. And I would argue that for a whole lot of people, their day-to-day interaction with the growing mass market was often manifest in how people ate.

JP: Tell me about the experience of building your project, and what you do on a day-to-day basis.

AI: The technical aspect of it—creating and maintaining the infrastructure and platform for the blog—is a huge and constant part of the day-to-day work.

JK: Posting things and tweaking things—it’s never done, it’s constantly in flux, with broken links or formatting problems.

JP: So, it feels more like technical computer work in a lot of ways? Your focus isn’t so much on going out and finding recipes and cooking food?

JK: I think it’s both. We work on the text of the posts, sending drafts back and forth and picking images for them. Cooking is actually the smallest part of it, time-wise.

AI: It’s very much like being a PhD student. You have to be self-motivated, push your project forward, have a clear idea of what you want to do. And you have to make people interested in your work—also relevant for academia. We spend a lot of time promoting the blog on social media and e-mailing food writers and trying to create an audience.

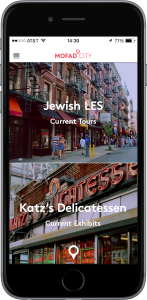

The MOFAD app will feature long-standing food establishments in various neighborhoods. Users will learn about the specific locations and how they relate to the history of various neighborhoods, and encourage people to interact with the businesses themselves.

JP: Speaking of connections to PhD work, Columbia has stressed History in Action as a way of honing in on the skills that historians develop. How have your projects helped you think about doing, writing, researching, and presenting history?

JK: Cooking is useful for thinking about how practices and knowledge are passed on, which is a crucial part of thinking historically. In one case, we made an “Easter pudding” from a 20th-century Jewish synagogue cookbook. When we started cooking, Alma was like, “What is this thing?” It had no bread, no flour. We realized that it’s a Passover pudding that was being called an Easter pudding, because they’re trying to market it to a non-Jewish audience. You might have missed that if you were just going through the book.

AI: On the blog, people spend their time reading something that I wrote, and I respect the time that they invest. This is very much like writing history. People give you their time, which is the most valuable thing they can give.

JK: Even the little bit of networking that we’ve done is so valuable as a life skill, and it’s fun to tell people about your work and get them excited about it.

MK: Yeah, pushing this project has helped me think about the process of the dissertation. We know intellectually that a good idea is only a small part of the process of making an influential historical argument. Being a good project manager for your own work might ultimately make a bigger difference in terms of success.

AI: You need to be in dialogue with “the reader” in your mind, to understand the demographics—gender, city, age—of whoever is reading what you’re writing. It’s thinking about the public in a very delicate, complicated way, understanding who the audience is and creating the audience as well.

MK: It’s important to remember that history projects that engage the public also make historiographical interventions.

AI: This project also builds community among historians. Writing for the blog, I get to talk to my colleagues and ask them to read Mesopotamian recipes. There’s something very strict about writing such a short text that I love, about staying with your argument and ripping everything extra out. Exercising different muscles, writing both tweets and a dissertation, is important.

JP: There’s a tension within the HIA endeavor that these are necessarily side projects. How have you guys fit the project in with the rest of your work?

AI: It’s been challenging. Each post takes about 30 hours. The way I first pitched the idea, I included expenses, but I didn’t really think through the value of my time, Jordan’s time, the time of my husband, who is our photographer.

JK: I spend every waking hour that I’m not doing other work thinking about this project! It’s a lot of time.

AI: Something like this blog, it’s not a sprint, it’s a long-term commitment. Things like the Ottoman History Podcast don’t just emerge overnight. It will be interesting to see if HIA can incorporate longer-term commitments like this into its future structure.

MK: A lot of people already volunteer with other organizations, or pursue side projects. Some people have always engaged in outreach, but for any number of reasons many might have had trouble establishing their own connections or finding time to volunteer. HIA provides institutional connections and some funding to make people’s existence as scholars, not just their dissertations, easier and more effective.

Jake Purcell is a PhD student in medieval European history at Columbia University. He serves as a co-coordinator of the department’s History in Action program.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Career Diversity for Historians Food and Foodways

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.