Ecological Explorations of Shaolin: Placing the “Ol Dirty Bastard Environmentalism” of the Wu-Tang Clan

Five years ago, as I began writing an environmental history of Staten Island, one of my advisors who grew up in New York during the 1980s paused at the end of our hour-long conversation. “But Pat,” he said, considering his words carefully, “what does all this history tell us about the Wu?”

By the Wu, my professor was referring to Wu-Tang Clan, the nine-man hip-hop group hailing from Staten Island—an MC ensemble that between 1993 and 1997 produced seven gold albums, revolutionized recording contracts, and published more lyrics than a lifetime of Bob Dylan albums.

His query was, as the kung fu-influenced Wu would put it, a koan: a paradoxical riddle designed to spark unconventional thinking. What does hip-hop have to do with environmental history?

Like a good koan, the question has poked and prodded for years. So this summer I set out to answer the riddle. I watched Wu-Tang documentaries; flipped through Wu comic books; perused Wu-Wear websites; studied the Wu-Tang Manual; and, of course, filled the summer with Wu-Tang albums on repeat (“Aaaaah yeah, again and again”).

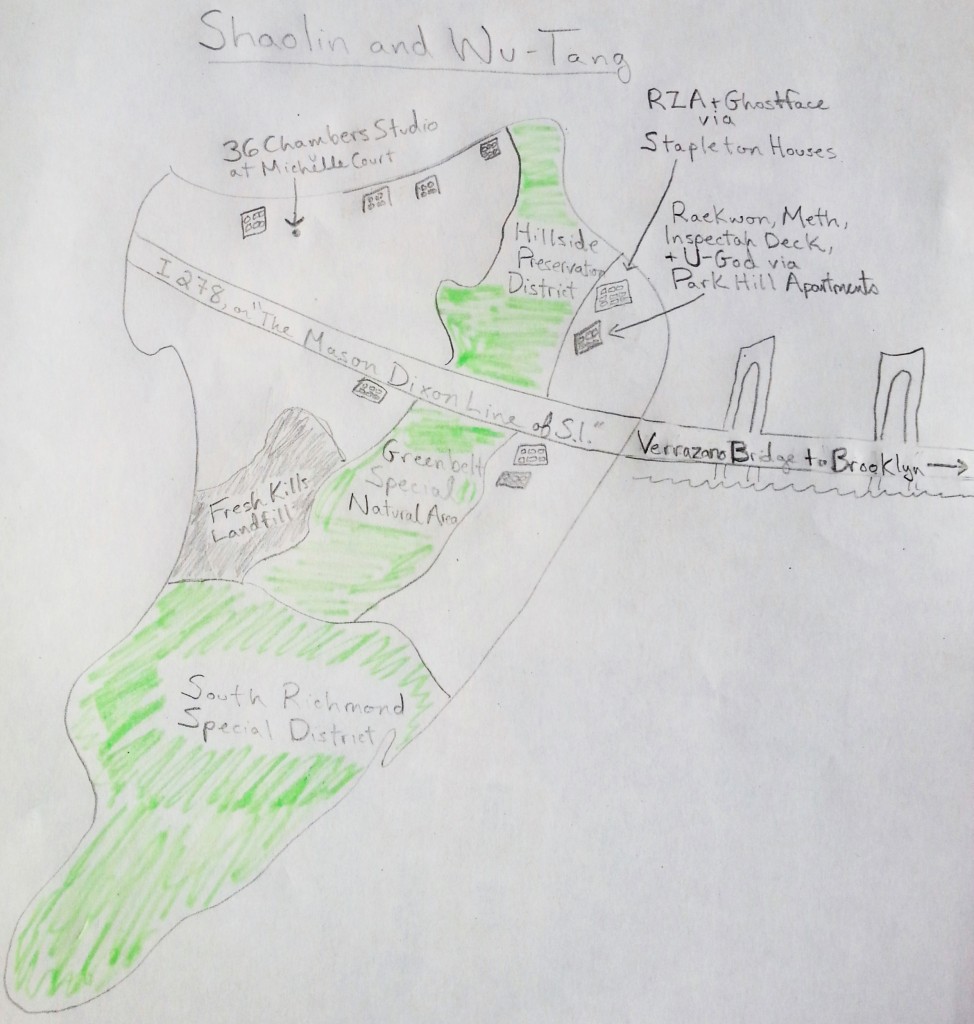

With the Wu-Tang catalogue as my archive, I mapped out where these nine MCs grew up and where they recorded on Staten Island, how they understood the urban environment, and what they perceived as their own niche within a larger borough they nicknamed “Shaolin”—a gesture to their favorite kung-fu flick Wu-Tang vs. Shaolin.

Many scholars have commented on the hyper-local nature of hip-hop—the music’s attention to street corner, turf, and neighborhood. Yet most interpretations tend to situate hip-hop within national debates over industrial flight, Reaganomics, police brutality, and mass-media representations of African Americans.

But to contextualize Wu-Tang within the highly segregated landscape of 1990s Staten Island is essential in distilling the group’s mysterious iconography. Placing them within this heavily polluted, yet heavily preserved borough reveals that the group’s exaggerated griminess—one of Wu-Tang’s most significant contributions to gangsta and horror rap—is best understood as a response to the specific environmental policies and rhetoric that had sequestered them in “the Shaolin slums.”

To do so also clarifies that hip-hop was (and is) not just a reaction to national politics and culture, but a grounded response to very tangible forms of oppression found in the contours of city planning maps—whether exclusive zoning codes, gerrymandered school districts, or unjust allocations of green space.

Background: Environmental Politics on Staten Island

Historicizing environmental politics on Staten Island reveals intense struggles over race and space in New York City just at the moment the hip-hop generation was coming of age. In the 1960s and 70s, for example, civil rights advocates sought to integrate southern Staten Island’s predominantly white, middle-class residential districts. However, as I discussed in my previous posts on the Staten Island Greenbelt and “Sandy Ground Cultural Park,” fair housing efforts were stymied by environmentalists supporting exclusive, ecological zoning protocols.

In the 1980s and early 90s, a secession movement bubbled up from these ecologically protected enclaves, calling for the borough to break away from New York City. Rallying around the symbol of Fresh Kills Landfill on the borough’s west coast, secessionists expanded anti-garbage metaphors in racially problematic ways. Staten Island had become a “dumping grounds” for a host of urban “undesirables,” Borough President Guy Molinari explained. Only through secession, the Staten Island Advance suggested, could the borough “stop the flow” of waste, crime, poverty, public housing tenants, and “general bad manners.”

Note the juxtaposition between the borough’s three sprawling special districts (in green) and the borough’s nine public housing sites concentrated on the north shore (Credit: Patrick Nugent)

In response, minority activists united with labor, liberal, and LGBT groups in northern Staten Island to fight secession. These groups described Staten Island as a segregated urban/suburban landscape bisected by I-278—what they called “the Mason-Dixon Line of the borough.” They argued that elected officials had long ignored their requests to discuss the borough’s segregated school system. They critiqued a “secession curriculum” distributed by the Advance as “an attempt to teach children prejudice.” [1]

Enter the Wu-Tang

In 1993, the same week that two-thirds of Staten Island residents voted to secede from New York City, Wu-Tang released its first album, Enter the Wu-Tang: 36 Chambers. Through a motif I like to call “‘Ol’ Dirty Bastard’ Environmentalism” (in honor of the late ODB), Wu-Tang developed a unique ecological rhetoric of its own, critiquing borough environmentalists’ misplaced priorities and highlighting the segregated nature of Staten Island projects.

Just as contemporary West Coast rappers had created overblown “gangsta” caricatures out of racist stereotypes, Wu-Tang MCs embraced rhetoric that likened their neighborhoods to “rubbish.” They described themselves as “raw,” “rugged,” “grimy,” and “nasty.” They had “funky breath,” wore muddy “slaveman boots,” and threw down rhymes “like a stink bomb.” They were, proudly and undeniably, “the dirtiest thing in sight.”

In its more playful moments, ODB environmentalism flipped the language of modern environmentalism to undercut the idyllic, nature-nostalgia of fellow borough residents. In Wu lyrics, “glaciers” came to mean cocaine, “white owls” meant blunts, and the “tiger,” “toad,” and “crane” were MC styles. Beloved characters of the environmental imagination were uprooted from the hinterlands with ODB flowing lower than “Jacques Cousteau,” RZA screaming “like Tarzan,” and Raekwon rocking “moccasins.” The rallying cries of secession lost their meaning: “garbage” signified watered down drugs and “Fresh Kills” was a place to stash a body.

ODB environmentalism didn’t just mock environmentalists, but turned their criticisms of modern society toward the segregated projects. Staten Island’s subsidized housing complexes were “science projects” according to RZA’s autobiography, where the forces of oppression infuse “even the air and water.” The Shaolin slums weren’t simply impoverished, but polluted, overpopulated, and unhealthy. “Snotty-nosed” kids share dirty laundry, squeeze into overcrowded beds, and pluck “roaches out the cereal box.” Drugs and viruses course through “blood streams.” Screams of terror “lightly rain” down upon the streets.

The mythology of Shaolin grounded the gangsta MC in his local environment, a place where science materialized into social structure. Wu-Tang’s lyrics peered deeply into the Shaolin projects, but in doing so, they also rubbed up against the borough’s ecologically protected enclaves, critiquing the politics and policies that drew lines between Staten Island’s places and people.

Whether Grand Master Flash’s “jungle,” De La Soul’s “pot holes in my lawn,” or Wu-Tang’s “Shaolin,” the environmental imagination of hip-hop has consistently undercut prototypical American landscapes. The suburban yards, pristine lakes, and primeval forests that surround and sequester the urban project are more often than not a subject of irony and transgression. That is to say, the hip-hop artist has long been an environmentalist—an Ol’ Dirty Bastard of an environmentalist—muddying pastoral myths, and singing landscapes that most environmentalists dismiss.

Notes

1. “Creating a New City: A Teacher’s Manual on Staten Island Secession,”Prepared by the Staten Island Advance, Norman Steisel Correspondence, Box 264, Folder 2500, Roll 130 “Staten Island, 1993, September-October,” Mayor David Dinkins Papers, Municipal Archives, New York City.

Previous Posts: Cycling Through the Greenbelt , Contemporary Landscapes and Archival Paper Trails, Ecological Explorations on Staten Island

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Perspectives Summer Columns African American History Cultural History Environmental History Urban History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.