“The Confederacy, Its Symbols, and the Politics of Public Culture”

AHA Plenary: January 7, 2016

A plenary is a meeting “attended by all participants at a conference or assembly.” The plenary at the 2016 AHA annual meeting was something more, and it gave the room a feeling different from plenaries in years past. This was a session attended not only by participants of the annual meeting; for the first time in recent AHA history, it was free and open to the public. Feeling in the overflowing room was heightened further by the region in which it sits: this was a session on monuments to the Confederacy, held in a former Confederate city.

And yet, the mood in Atlanta was neither tense nor self-righteous, neither bellicose nor smug. Taking their cue perhaps from AHA executive director James Grossman—who counseled “humility” in his introductory remarks—the session’s five speakers seemed chastened by the task at hand: what to do about a southern landscape crowded with Confederate statuary and flags that are beloved by some, but intolerable emblems of white supremacy to others. As panelist John Coski of the American Civil War Museum reminded listeners: “whatever you personally think of it [the Confederate flag], you know that not everyone agrees with you,” adding, “Wouldn’t it be a good idea to understand where they’re coming from?”

Commemoration is complicated, communal work. Americans first confronted that work at Gettysburg, with the terrible task of identifying fallen soldiers. “After great pain,” Emily Dickinson had written a year prior, in 1862, “a formal feeling comes.” Formalizing the Civil War dead, panelist and George Mason University professor Jane Turner Censer reminded us, was quite often women’s work—“civic housekeeping” intended to impose “order and tranquility to a landscape” strewn with dead bodies. That modest commemoration was less problematic by Censer’s reading than the grand, celebratory statues that came later. “Societies find different ways to remember the dead,” said Censer, and Civil War commemoration changed over time from a process of “gathering the dead in cemeteries, to glorifying the heroes of the confederacy”—turning private grief into public provocation.

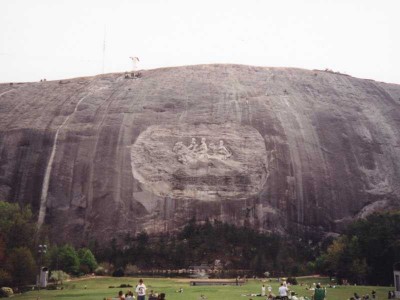

Consensus that some of that statuary now “needs to go” is easier established than consensus on what, specifically, should go. UNC Chapel Hill’s Fitzhugh Brundage put it this way: there are statues “we should remove. And then there are those that we would perhaps want to reinterpret. And then there are those that we will probably end up deciding that we have to tolerate.” Take Stone Mountain, a half hour’s drive north of our annual meeting: the world’s largest piece of exposed granite, into which massive carvings of Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis on horseback were completed in 1972. Brundage called it an “elaborate shrine to white supremacy” but couldn’t see a viable way to either demolish or transform it. Still: small steps matter. If Brundage once believed that we should “concentrate on more important things” than memorials, he has come to see “the effort to revise the commemorative landscape of the south as part of a much larger project to create a more pluralist south.”

Those difficult choices about what to add (the Arthur Ashe statue on Richmond’s Monument Avenue, for instance), what to move, and what to rename were the specific tasks charged to a panel convened recently at UT Austin about its own campus statuary. Daina Ramey Berry, a professor at UT and a member of that panel as well as the plenary, came away from the experience asking, “what is the historian’s charge?” Berry brought photos of the University’s Jefferson Davis statue taken two months before it was moved across campus (from the South Mall to the Briscoe Center for American History—or, as center Director Don Carleton put it, “from a commemorative context on campus to an educational one”), with the phrase “Black Lives Matter” spray-painted across its base. “If we don’t want to deal with this,” Berry cautioned a room full of historians, “activists will.”

Plenary chair and Yale historian David Blight noted that “in memorialization, loss is always more interesting than victory.” If he’s right—and as the city of Charleston ponders how best to memorialize the nine men and women killed at the Emanuel AME Church last June by an assassin who had posted pictures of himself with the Confederate flag—one hopes that our days of memorial building will one day be behind us. The Reverend Clementa Pinckney, Blight recalled, had possessed “a beautiful baritone singing voice.” Would that we could hear that voice rather than attempt to commemorate it.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today 2016 Annual Meeting North America African American History Public History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.