This post marks the second in a series on what we’ve come to call the Career Diversity Five Skills—five things graduate students need to succeed as professors and in careers beyond the academy:

- Communication, in a variety of media and to a variety of audiences

- Collaboration, especially with people who might not share your worldview

- Quantitative literacy, a basic ability to understand and communicate information presented in quantitative form

- Intellectual self-confidence, the ability to work beyond subject matter expertise, to be nimble and imaginative in projects and plans

- Digital literacy, a basic familiarity with digital tools and platforms

Collaboration seems like a straightforward skill, often simplified as the ability to work in teams or to play well with others. It certainly is a familiar concept, popular and widely accepted as a valuable educational approach in secondary and higher education. At the same time, collaboration is a somewhat contentious idea in the training and work of academics, both of which heavily privilege individual scholarship and accomplishments. In the humanities, the idea that co-authored articles and books are valued less in the tenure process is largely accepted as a truism. In recent years, the increased number of digital humanities projects has brought the question of how collaborative work should be evaluated, acknowledged, and valued to the front and center of academic debates. So, perhaps collaboration is not as simple and familiar as it appears.

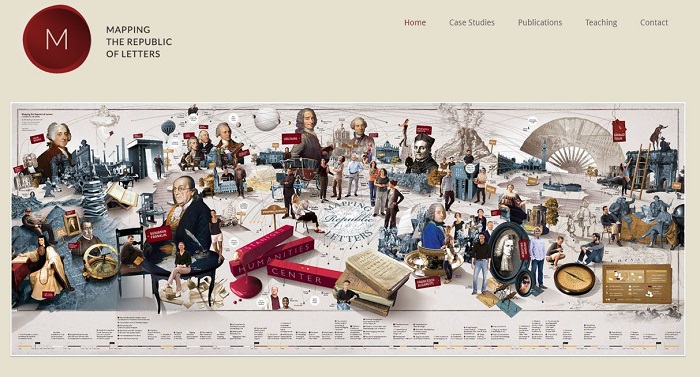

Collaboration requires practitioners to recognize when a problem or a project is too large or complex for one person. Digital projects such as Mapping the Republic of Letters require extensive collaboration, and include a range of partners who contribute to different aspects of a project in order to achieve a common goal.

I came to my graduate program in history with extensive experience in the corporate and nonprofit worlds where collaboration was the norm—the way I tackled nearly all of my responsibilities. As a graduate student, I was struck by the heavy, nearly exclusive emphasis on the solo effort, the individual project. I missed the camaraderie and diversity of working with 3 or 10 or 20 other people, all equally invested in solving the same problem or achieving the same objective.

It took me a while to understand that collaboration in the academic context often happens on a different scale and is described in different terms: we organize conference panels and colloquiums, work with editors to polish an article or book manuscript, co-teach courses with colleagues, serve on departmental search committees, plan and coordinate community oral history projects, create digital publications, etc. I realized that inside and outside the academy, what constitutes collaboration—what it is, its value, and how to practice it—takes many forms. There are, however, three essential elements that remain consistent. Collaboration, even in academia, is

- a series of activities, not simply a one-time task;

- undertaken with others, not alone; and

- for a shared, mutually understood and valued objective, not for exclusive or singular benefit.

Collaboration requires practitioners to recognize when a problem or a project is too large or complex for one person. It allows us to appreciate the value of diverse experiences, perspectives, and skills needed for solving problems and getting things done. Collaboration also requires that one be present for and engage in the necessary conversations that facilitate defining common goals, optimum roles, and appropriate responsibilities. Meaningful collaboration creates trust, inspires innovation, fosters learning, and encourages flexibility. Because of all this, for at least a decade, growing consensus across employment sectors has held that collaboration is a crucial aspect of any and all work undertaken. In fact, it regularly shows up on “top skills employers want most” lists. Graduate students and early career historians can (and do) demonstrate their collaborative skills to potential employers by highlighting their experiences as participants in graduate student groups and leadership teams, as well as in organizing conferences and publishing projects.

As a graduate student and postdoc, for example, I curated a major museum exhibition and initiated a multi-source, multi-authored digital history project, working with a variety of organizations and people. Being a curator involved not only creating the exhibition narrative that was peer reviewed by other historians, but also participating in sessions with artifact lenders, preservationists, designers, and marketing experts to produce the “look and feel” of the show. After graduation, when I applied for the position of graduate career officer in the UCLA history department, my resume emphasized the collaborative experience I gained on these projects. I found this to be the most effective way to demonstrate that I could work on complex projects and that I had the ability to work with diverse groups of peoples and organizations—all requirements for the graduate career officer position.

Collaboration also has value beyond its popularity with employers. In the early 2000s, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (supporter of the AHA Career Diversity for Historians initiative) funded collaborative programs in support of faculty career enhancement at 23 colleges. Those programs led to a number of tangible and intangible outcomes, including new curricula and increased student learning opportunities, qualitatively better publications, expanded faculty networks, new grant opportunities, “enhanced community and collegiality,” and “renewed and reenergized faculty.” The program evaluators concluded with the following insight: “Creating conditions that encourage faculty collaboration is an important way for higher education institutions to innovate and adapt in a time of rapid and continuous change.”

This insight is important to graduate students for two obvious reasons. First, innovation, productivity, connectedness, and renewal are all important outcomes for institutions and individuals intent on surviving, thriving, and influencing others. Opportunities to collaborate in graduate school can help mitigate isolation, stress, insecurity, and other feelings that often hamper progress toward degree completion and preparation for employment. Second, innovative digital scholarship—increasingly ubiquitous at the AHA annual meeting—and public humanities initiatives and collaborative projects championed by the Mellon Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and others are advancing its belated acceptance in academia. Collaboration is the future.

Perhaps the most significant value of collaboration is that it produces a shift in the attitudes and actions of practitioners. In my own experiences of creating museum and digital exhibitions, developing and teaching new courses, and coordinating programs and conferences, authentic collaborations have offered an unexpected benefit—genuine and immediate feedback about my skills as a communicator/storyteller and a translator of historical research and insights. It has been among other collaborators that I have honed my appreciation of the diversity of the human experience and the value of human agency. Collaboration allows us to build bridges from the life of the mind we are trained to cultivate to the world of humans we live in. Simply put, to collaborate is to connect.

For more information on collaboration and the rest of the “five skills,” check out our new page www.historians.org/fiveskills and the rest of the contributions to this series.

Karen S. Wilson is the UCLA history department graduate career officer and holds a doctorate in US history.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Career Diversity for Historians Resources for Graduate Students

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.