In the October 2015 issue of Perspectives on History, I wrote on historically informed performance of medieval, Renaissance, and baroque music. Musicians at the Folger and Newberry Consorts spoke to me about how history informed their music, and in turn how music could help transport listeners to a different time.

At the National Council on Public History annual meeting in Baltimore last month, I once again found myself at the intersection of music and history at a workshop called “Banjos in the Museum: Music as Public History.” Organized by the Stevenson University public history program, this workshop featured archivist and musicologist Greg Adams and instrumentalists Ken and Brad Kolodner. Any attendees who expected the session to start with the usual reading and shuffling of papers were pleasantly surprised when it opened instead with a brisk bluegrass tune.

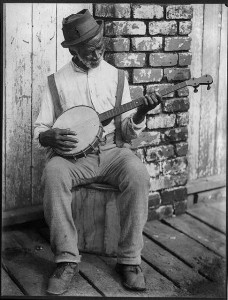

An elderly African American man playing a banjo, c. 1902; Library of Congress

The blithe strains of Adams and the Kolodners’ opening reel, however, belied the banjo’s complicated history. As Adams explained, the banjo is an instrument of African origin, recreated in America by displaced enslaved Africans. The banjo did not become popular with white Americans until the 19th century, when the instrument became a central feature of minstrel shows, played by performers in blackface. Ironically, it was minstrelsy that commercialized the banjo, making it a widely popular instrument. William Boucher began building and selling them in the 1840s in Baltimore, which itself became a hub of banjo production. With its adoption by Anglo-Americans, the banjo itself changed. The instrument’s body was no longer formed out of a gourd but a wooden hoop, and a fifth string was added. By the 20th century, the banjo and its music had changed dramatically and become associated with white southern culture.

Many audience members who enjoy banjo music, however, do not know this history. The Kolodners regularly incorporate the banjo’s history into their programs, and Brad Kolodner recounted the surprise many people express on hearing it. Adams has noticed a similar lack of awareness when he performs; at one nursing home he played at, residents began singing along—but with lyrics dating from the tune’s use in minstrel shows.

How can historians relate this and similarly complex cultural histories to diverse audiences? Specifically for the banjo, how can they address a history so heavily impacted by racism? This session was not only full of beautiful music, but it ultimately sparked intense discussion among attendees, beginning with the banjo’s appropriation by white culture. One audience member expressed concern that white performers playing music of Irish and Appalachian origin on the banjo threatened to obscure the instrument’s African roots and further alienate the black community. Another disagreed, saying that as long as performers played well, race shouldn’t matter. Everyone agreed, however, that this is a story that historians must tell, and they actively traded ideas about how to do so.

Discussion then turned to museum exhibits. Adams pointed to the 2014 Baltimore Museum of Industry exhibit, “The Banjo in Baltimore and Beyond,” as one successful effort at introducing the public to the banjo’s history. A co-curator of the exhibit, Adams was initially concerned about displaying racist ephemera, such as a poster advertising a minstrel show, so prominently; it took a leap of faith to bring this sensitive history before the public’s eyes. However, he said that in the context of the exhibit, visitors were receptive to discussions about this history. By incorporating posters alongside maps where banjos had been made and played in America—and the banjos themselves, of course!—the curators allowed museum attendees to see many facets of the banjo’s history at once, and therefore appreciate its full complexity.

The other challenge attendees discussed was attracting visitors to the exhibit in the first place. This is where collaboration between historians and artists comes into play. Adams suggested musical performances and related programming held on location to draw people in to the exhibit.

While historians face an uphill battle when telling a history of something performance-oriented like the banjo that has become such an integrated part of popular culture—to the point of its original roots being largely obscured—they nevertheless have some valuable tools at their disposal. Telling the history of the banjo is challenging, first, because it is an instrument that everyone thinks they understand because of its ubiquitous presence in American folk music, and second, because its real history is so interwoven with America’s painful history of race relations. However, historians also have the human love of music and performance to help them tell this story. They simply have to find creative ways of bringing the two together.

For a quick review of the banjo’s history and the 2014 exhibit, see Jerad Walker’s review for WAMU 88.5 American University Radio, “From West Africa to Baltimore: New Exhibit Explores the History of the Banjo.” To experience this music yourself, check out the Kolodners’ upcoming performance schedule.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Cultural History Public History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.