AHA member David Trowbridge, associate professor of history at Marshall University, was recently awarded the Whiting Public Engagement Fellowship. Granted by the Whiting Foundation, the fellowship funds a six-month leave for a recently tenured professor in the humanities to work on a “public-facing project.” Trowbridge plans to use the fellowship to work on Clio, a web and mobile app that identifies a user’s geolocation to deliver historical information about the surrounding area through text, images, and video. AHA Today caught up with Trowbridge recently and spoke to him about Clio and his future plans for the app.

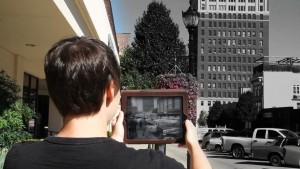

Clio connects the public to nearby historic sites and museums. It also reveals information about historic events that occurred near one’s present location. For example, this student is watching digitized footage of a civil rights protest that occurred at this location in 1963. Courtesy David Trowbridge

What is Clio, and what does it do?

Clio is a nonprofit foundation that seeks to connect people to the history that surrounds us. The Clio website and mobile application combine GPS technology with information about a growing number of historical and cultural sites around the United States. These two platforms pinpoint your location and allow you to discover information about historical events as well as nearby museums, cultural sites, historic buildings and landmarks, monuments, and other points of interest. Recognizing the limitations of historic markers carved into stone and metal, Clio entries seek to offer additional information, diverse perspectives, and links to related primary and secondary sources. Each entry should provide a compelling and concise summary, along with images and suggestions for additional learning via related books, articles, and websites. Entries may also include videos, oral histories, and other media.

The site has grown to include over 10,000 entries thanks to scholars, libraries, historical societies, and instructors who have created entries with their students, but we are just scratching the surface of what it possible. As a public history project, we are especially eager for contributions from local residents. We have created a modified system of crowdsourcing where these entries and suggestions are placed in draft mode subject to review.

What inspired you to create Clio?

The idea hit me as I was attempting to “discover” a city in those few hours we allow ourselves while attending conferences. I was curious about each building and monument, but in most cases, I did not have enough information to perform a useful Google search. After a few searches and a dozen pop-up ads, I gave up and decided to find something to eat. That search was easy, of course, thanks to mobile apps that offer concise and useful information about restaurants and businesses.

I spent a year trying to convince Yelp! and a few other companies to offer a platform for historians. Rather than provide ratings and reviews, this platform needed to connect curiosity with expertise. As it turns out, companies are not keen to build platforms that direct their users to other websites. Rather than give up, I built Clio as a free site dedicated to promoting the work of others. If I built the platform, I knew that people who care about history would add good content.

Did you discuss the project with your colleagues/chair before diving in? Were there any concerns about spending time working on a digital project, and whether it would count toward tenure?

My chair has always been supportive of my work and Marshall allows a tremendous amount of freedom. Despite this, I only discussed the idea with my wife. At the time, I had two manuscripts nearing completion and did not have tenure. I tested the idea by building a prototype with local entries from students and kept working on everything else. That semester, I noticed students were more engaged in this assignment than their exams and research papers. Many seemed to enjoy the project, and some of the students were using the prototype in their free time with their friends. When students came back from spring break with stories about visiting historic sites in their hometowns, I stopped everything and concentrated on Clio.

While most people are impressed with what Clio has become, what I did was a little reckless. I had no institutional support and my chances for securing a grant were so small that I did not even apply for funding for the first two years. The best advice I can give to someone willing to proceed under those conditions is to stay “too small to fail.” Live within your means and work on the project every day without neglecting the rest of your work. A project born and sustained by that kind of passion might crash and burn, but if you can keep it going on your own and find a couple wins along the way, it will surely outlast a project that required grant funding just to get started.

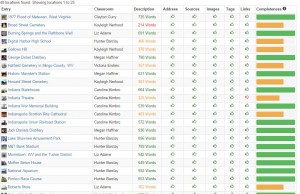

Clio provides special administrative accounts that allow instructors to create, edit, and publish entries with their students. The system allows for peer review, and provides tools so the instructor can review the status of each entry and the overall project. When the instructor approves an entry, it includes credit for the author, instructor, and the institution. Courtesy David Trowbridge

How would you describe your experiences with crowdsourcing? How do you guard against inaccurate or biased information?

The tech keeps getting better, but the greatest challenge is creating and editing content. Clio is a public history project, and members of the public will always be encouraged to contribute content and suggest revisions. After experimenting with an open model, we constructed a modified version of crowdsourcing where volunteers vet new entries and review suggested improvements. We also give editing privileges to trusted contributors and provide special administrative accounts for historical societies, museums, libraries, and other organizations so that they can create and improve entries with their members. (All of these accounts are free, and the entries created in those accounts go into draft mode pending review from the individual(s) who administer the institutional account.)

We hope that this modified version of crowdsourcing blends the potential of “open” with the need for review by professional historians and their students. For all of its challenges, keeping a public history project open to the public provides a diversity of perspectives and the ability to share information beyond the limited numbers of professional historians. It also assures that Clio offers content that serves the needs and interests of the public.

Have you used Clio in your teaching or with your students? If so, how do you use it? Do you have recommendations for how teachers could integrate Clio into their teaching?

The fact that my students used the early version of Clio to connect with history in their spare time is what drove me to hire professional developers. I have used Clio from introductory surveys to graduate seminars, and have learned a great deal about local history and other topics in the process. Students value the opportunity to share what they learn and add something to their resumes. More importantly, they learn how to conduct research and work diligently to improve their writing skills.

Like any research project, it is essential to include multiple deadlines for research and revision. I usually ask students to create three entries, with one of those entries being a “capstone” entry—something that requires archival research, the recording of oral histories, the creation of a video, or something that requires digital skills or transcription. After some initial trepidation, students discover and create something beautiful.

Recognizing that installing special software and remembering credentials and passwords were hurdles for students and headaches for instructors, we created “Clio in the Classroom” to make the project easy to manage. Rather than requiring students to create accounts, the instructor account allows one person to manage the work created by others. When students login to the classroom account, they can create and edit entries in draft mode. Students and instructors can provide feedback, and the instructor can monitor each student’s progress and publish their entries when they are ready. As of spring 2016, two dozen instructors have used Clio in the Classroom. It is an ambitious project, but these instructors report tremendous satisfaction and pride in their student’s work.

What are your long term plans for Clio? How do you intend to use the Whiting fellowship?

In the coming years, we will need to integrate Clio with technologies that do not yet exist. That’s the easy part. Creating interactive history tours in every community, on the other hand, will require tens of thousands of entries that have not yet been written. If we are successful in this endeavor, and if we can blend original and compelling content with a delivery system that reaches people where we stand, we can show that history matters. As one of my students reported, using Clio led her to recognize that everything in her town had a history and most of those histories were connected.

The Whiting Foundation fellowship will allow me to spend the next six months building support materials and instructional videos for instructors, historical societies, libraries, and individual contributors. I will also create and improve entries related to the long civil rights movement. I also hope to work with historians to interpret Civil War monuments and other complicated and contested histories.

This fellowship will also support the creation of new features such as interactive walking and driving tours. The new system will allow users to create and share preset tours as well as create personalized itineraries. Right now, mobile apps offer walking tours that require people to start and stop at a preset location and follow a preset route. The system we are creating will allow users to start one of these tours from any location. They will also be free to adjust the tour to fit their schedule and interests.

Do you have any tips for other historians looking to develop digital apps? Where would you recommend them to start? What skills should they seek to develop?

No one person can build and maintain an ambitious public project like this, so the first step is to find others who feel the same way as you do. Take some time to think about what success might look like—ask yourself if you are willing to devote that kind of time to the project before you get started.

We talk a great deal about the potential for apps and other digital projects to reach the public, but sometimes we fail to include ourselves as part of this “public.” Do not simply create something you imagine other people might use, build something you would use—not just in the classroom or for your research—but in your personal life. If the project you have in mind would benefit from having a mobile app, ask yourself how you might first start without taking this expensive and time-consuming step.

Any final thoughts?

Clio gets a little better as students and instructors create and/or improve entries. History is complicated, so I built the system to be simple and intuitive. If you would like to use Clio with students or members or your organization, you can sign up for an instructor or institutional account at www.theclio.com. Clio also provides internship opportunities for motivated students who create and improve entries related to their areas of interest. If you have students who may be interested in this internship, or if you would like to support the project or partner with us in future projects and grant applications, please contact me at david.trowbridge@marshall.edu.

David Trowbridge (PhD, Kansas 2008) is an associate professor in the department of history and director of African and African American Studies at Marshall University. A leading advocate of the potential of free and low-cost educational materials, Dr. Trowbridge is also the author of A History of the United States (2012). He is also the creator of Clio, a website and mobile application that connects thousands to information about nearby historical and cultural sites.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Digital History Public History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.