This post marks the fourth in a series on what we’ve come to call the Career Diversity Five Skills—five things graduate students need to succeed as professors and in careers beyond the academy:

- Communication, in a variety of media and to a variety of audiences

- Collaboration, especially with people who might not share your worldview

- Quantitative literacy, a basic ability to understand and communicate information presented in quantitative form

- Intellectual self-confidence, the ability to work beyond subject matter expertise, to be nimble and imaginative in projects and plans

- Digital literacy, a basic familiarity with digital tools and platforms

Numbers are everywhere. Especially in the midst of election season, one wakes up every day to a new poll, a new survey, a new forecast. In times like these, historians have an important role to play—they can break down the numbers, offer meaningful and critical interventions, and provide historically accurate information. More than ever, a publicly engaged historian now also needs to be a quantitatively literate historian.

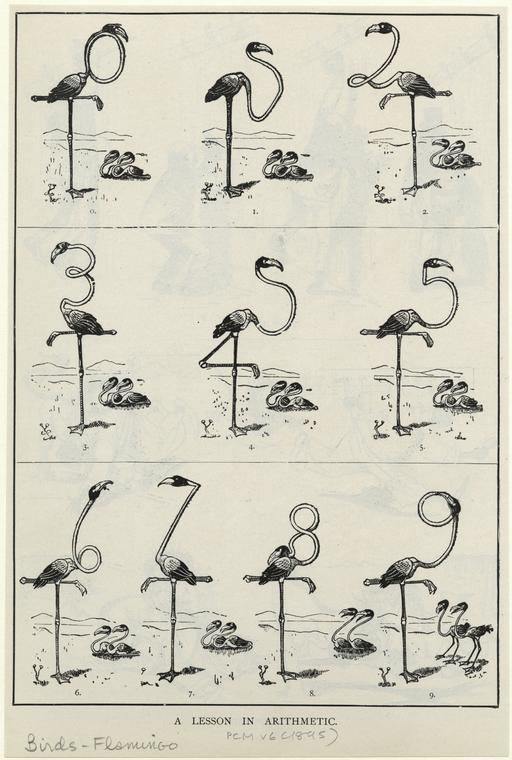

Don’t get all twisted trying to learn numbers! Quantitative literacy is a much more basic skill that allows historians to understand as well as communicate ideas and concepts not always easily explained with words. Image: “A Lesson in Arithmetic” (1895), The New York Public Library Digital Collections

But what if math has always been your pet peeve and you thought that entering grad school in a humanities program had definitely shielded you from those annoying numbers? Who is this pesky person trying to convince you of the importance of numbers and being quantitatively literate? In other words, what if I am really afraid of numbers and not willing to engage with them because I took a vow to never again utter that which shall not be named (vectors)? And didn’t the GRE (yet another humiliating rite of passage) provide enough trauma?

We are here to tell you not to worry. Numbers are now much easier to play around with! And acquiring quantitative literacy does not require you to become a math wizard. Quantitative literacy, in fact, is a much more basic skill that allows historians to traffic in ideas and concepts not always best or most easily explained with words. It also represents the ability to appreciate or understand quantitative methods in historical research. Quantitatively literate historians do not shy away from numbers, charts, or graphs—they use their critical minds and historiographical training to contextualize the numeric information in front of them and interpret it.

Much like Robin can do for Batman, numbers can help historians test long-held assumptions and provide a solid basis for histories of representation and discourse. Many historians, in fact, already use numbers and data in their research. Tax rolls, census data, electoral records, business ledgers—all constitute examples of numeric primary sources that historians use regularly and that can influence the kinds of research questions they ask. Numbers can also facilitate cross-discipline discussions and collaborations with political scientists, economists, and sociologists, among others. So one can also think of numbers as an important travel visa within the academy. For those with bad travel experiences who worry numbers pose the same threat as street vendor sushi, rest assured: numbers need not always drive the narrative; they can serve it by making it more illuminating and more compelling.

Even beyond the use of numbers in research and public engagement, graduate students would be well served to think of quantitative literacy as a precious career diversity skill. Numbers, in fact, play a significant role in the everyday work of most historians, and achieving quantitative literacy can help you become more efficient in your regular job. Be it in writing grant applications, critically analyzing student evaluations, creating budgets, conducting program assessments, analyzing web traffic, or managing databases, command over numbers is an increasingly valuable skill for historians to possess, and that potential employers look for.

But how does one learn to be quantitatively literate? And what if one is afraid of math? Many graduate students in the humanities go through this kind of angst, and yet it need not be an obstacle to using numbers productively. Quantitative literacy is not some sort of a litmus test for who is a “scientist” and who is a “humanist.” Understanding numbers is primarily about being able to read quantitative sources in a productive way. It is about understanding what the concrete things and processes are that numbers describe, that is, how numbers create categories and concepts. Those seeking more advanced skills could seek out a basic statistics course or attend dedicated boot camps like Cornell’s History of Capitalism Summer School, but unless your research requires you to learn statistics (which was our case), the most crucial thing to do would be to simply not shy away from numbers and to take them head-on.

During the AHA-sponsored Money, Numbers, and Power (MNP) seminar that we organized at Columbia University during the spring semester of 2016, we worked to foster a modicum of intellectual self-confidence among history graduate students in the Greater New York area interested in economic subjects. Promisingly, historians are part of the recent post-crisis resurgence of interest in economic issues both within and outside the academy (take for example the work being done by the Institute for New Economic Thinking, the co-sponsor of the MNP seminar), and they are willing engage with numbers and figures when we encounter them in our research or in our work.

Becoming familiar with numbers, and including more quantitative-based methods in qualitative research, is a way to expand the realm of possibilities for the historian. Our work is bound up with the societies that we inhabit, and this means that today, the study of the past in the light of the present demands an understanding of the language of numbers. Quantitative literacy is a crucial skill to many extra-academic careers, but it will serve you well as a historian no matter which career path you select.

For more information on quantitative literacy and the rest of the “five skills,” check out our new page www.historians.org/fiveskills and the rest of the contributions to this series.

Madeline Woker is a PhD student in international and global history interested in the political economy of French imperialism and the economic history of Vietnam. She works on the history of taxation and inequality and has been writing about the politics of taxation in the French empire, with a focus on Indochina. Nicholas Mulder is a PhD student in modern European and international history at Columbia. He is working on a history of economic sanctions from 1914 to the 1950s with a focus on Britain, France, Germany and the United States.

During the 2015–2016 academic year, Madeline and Nicholas partnered with the Institute for New Economic Thinking and the American Historical Association to foster economic history research within Columbia’s history department. They organized a seminar series and a reading group entitled “Money, Numbers and Power.”

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Career Diversity for Historians Resources for Graduate Students Digital History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.