The Rise of Dalit Studies and Its Impact on the Study of India: An Interview with Historian Ramnarayan Rawat

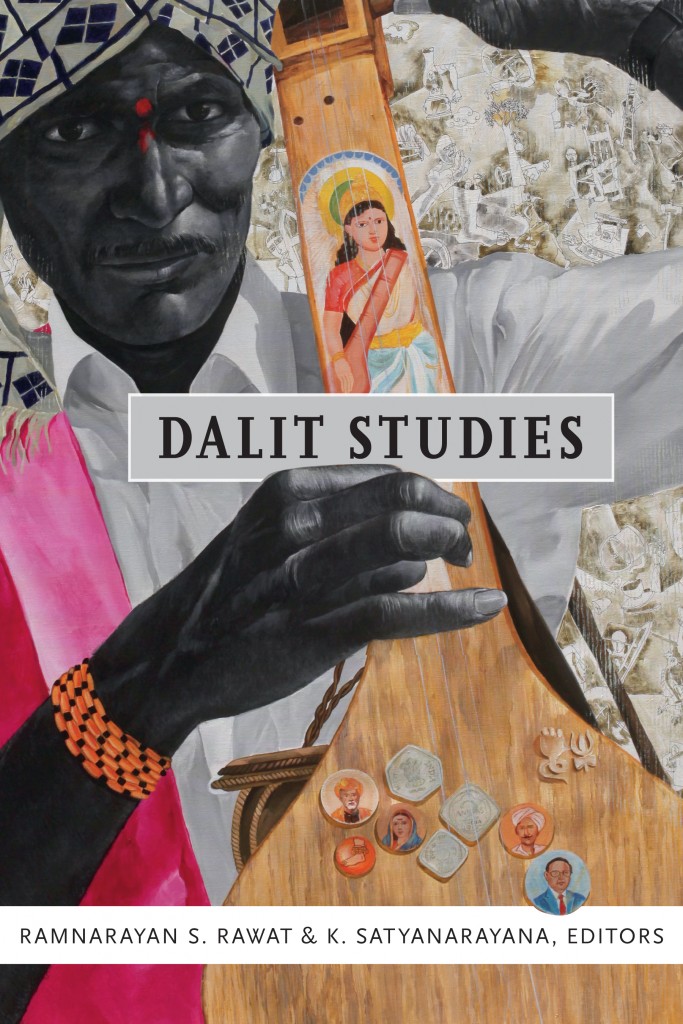

Last month, controversy erupted again in California over the portrayal of the South Asian subcontinent in history textbooks. Among the disputed points was whether schools in California should teach Dalit history and the history of the caste system to students. While the word “Dalit” may ring unfamiliar to most outside the subcontinent, Dalit history is a burgeoning field of study in academia, both in the United States and India alike. We caught up with historian Ramnarayan Rawat (Univ. of Delaware), co-editor of the recently released Dalit Studies (2016), to ask him what Dalit studies is and what the future of the field looks like.

For those of our readers who might be unfamiliar, can you briefly explain what the word “Dalit” means and who Dalits are?

For those of our readers who might be unfamiliar, can you briefly explain what the word “Dalit” means and who Dalits are?

Dalit is a Sanskrit word which means “oppressed” and “downtrodden.” It was appropriated in the 1970s by “untouchable” writers and activists to describe their community, both in the present and in historical contexts. Starting with the Dalit Panther movement, led by writers in the 1970s, the term “Dalit” acquired a radical new meaning of self-identification that signified a new oppositional consciousness. Today it is a widely used term in the Indian public sphere, especially in academic and literary fields.

Dalits constitute nearly 17 percent of India’s population—210 million people as per the 2011 census. They are considered untouchable by orthodox Hindus and Hindu theology because of their association in rural areas with impure occupations such as leather work, sanitary work, removing dead animals, and midwifery. In addition, because Dalit communities have been historically segregated, the practice of untouchability has a distinctive spatial dimension. The practice has moral and religious sanction in Hindu theology.

What are the major goals of the field of Dalit history or Dalit studies? What are some of the reasons behind the emergence of Dalit studies as a field of inquiry?

The major objective of Dalit studies is to offer new perspectives for the study of India. First, to foreground dignity and humiliation as key ethical categories that have shaped political struggles and ideological agendas in India. Second, Dalit studies historicizes the persistence of caste inequality and discrimination that have acquired new forms in a modern and democratic India. Given these objectives, a key aim of Dalit studies is to recover histories of struggles for human dignity and caste discrimination by highlighting Dalit intellectual and political activism.

There has been a general absence of research into and engagement with the perspectives of 20th-century Dalit intellectuals such as Swami Achhutanand, Bhagya Reddy Varma, Kusuma Dharmanna, and Iyothee Thass. The rise of Dalit studies as a discipline can be located in the transformational political events of the 1990s in India: The greater visibility of Dalit political movements, especially the Bahujan Samaj Party’s rise to political power in the 1990s and 2000s in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh; the rise of new and visible Dalit movements in southern Indian states such as Tamil Nadu; renewed discussions around caste inequalities and discrimination following the Indian government’s decision to implement recommendations from the Mandal commission report to extend affirmative action to lower caste groups; and the emergence of a new group of Dalit activist/intellectuals in universities across India.

What are the challenges of doing Dalit history, both from theoretical and methodological standpoints?

The challenge is to make Dalit agendas and actors visible. This requires innovative approaches and combining anthropological, historical, and literary fields. In my research I have found politically and culturally informed discussions in spatially secluded Dalit neighborhoods to be the most productive. I have found their viewpoints and agendas rarely acknowledged in mainstream academic contexts, and have followed up on them in historical, archival, and literary sources.

For example, many Dalits, considered impure because of their association with occupations such as leather working in their neighborhoods in northern India, told me that historically they have always held land and been peasants. I was able to corroborate these claims in historical registers, which equipped me to think anew about Dalit agendas in the early 20th century. Likewise, Dalit activists and groups have always claimed that they have an ethical commitment to ideas of equality and democratic politics. Dalit owned printing presses in the 1920s published books that addressed these questions and related them to heterodox religious practices in their neighborhoods.

Why should scholars outside of South Asian history pay attention to Dalit history? What sorts of courses do you think would benefit from readings and discussions on Dalit history?

Dalit history illustrates and enables connections with global histories of racism and social exclusion. Scholars (and students) will find remarkable parallels on policies and practices that sustain exclusion of Dalits (similar to black people and Burakumins in Japan), and their struggles to seek access to public spaces. For these reasons, courses on race and ethnic studies, Africana studies, black studies, history, anthropology, English/postcolonial studies, literary studies, and area studies can benefit from Dalit histories. Courses that emphasize innovative methodological and theoretical approaches will find Dalit histories useful, especially for graduate students.

In the introduction to your book, Reconsidering Untouchability, you argue that “Dalit perspectives on Indian history have little respect for the framework of colonialism versus nationalism mapped by Hindu-dominated mainstream Indian historiography.” Can you explain what you mean by this and also elaborate on your critique of Indian historiography?

In mainstream Indian historiography the framework of colonialism versus nationalism highlights the major contradiction that has shaped the making of modern Indian society. In this conceptual framework, colonialism is regarded as the homogenous and primary form of oppression and exploitation of all Indians. The framework has helped the Hindu nationalist elite to appropriate both history and power in modern India. The historiography centers anti-colonial struggles of the Hindu nationalist elite at the expense of other forms of activism or social concerns. Dalits, tribal groups, and women’s organizations, for example, often responded very differently to the presence of colonial rule in India.

Dalit history demonstrates that the colonial legal regime provided Dalits with mechanisms to claim political and constitutional rights previously denied to them. The colonial state’s legal apparatus, consisting of judicial courts and the police system, allowed Dalit activists and groups to demand access to public spaces and gain employment in new professions, such as the army and state bureaucracy. Dalit activists also considered the practice of untouchability and the persistence of caste hierarchies as crucial questions central to decolonization. Led by B.R. Ambedkar, Dalits urged the British and the Indian National Congress to give them adequate representation in constitutional discussions regarding the transfer of power to Indian representatives and the establishment of a new constitution.

What does the future of Dalit studies look like? What are some of the new trends in the field?

Dalit studies has the potential to fundamentally alter the historiographical map of India/South Asia studies. The recent recognition by Indian academia of Ambedkar as a philosopher and social scientist who made important contributions to the study of Indian society and history, the surge in Dalit histories in the last decade all around the academia, especially in the United States, all seem to suggest that a new set of questions are informing research and the study of India.

A key trend in the field is to recover histories of leading Dalit activists or leaders in different regions of India and to explore the nature of activism that emerged there. A second prominent trend, which I have not mentioned so far, is to recognize the distinctive agendas of Dalit feminism. A third emerging trend has been to engage with Dalit literature, in both prose and verse forms, as well as political and autobiographical writings, to understand the cultural and social motivations that have shaped their political activities. A fourth prominent theme is to study Dalit groups’ religious and cultural formations. These four trends draw from, and build on, the work done by scholars prior to the 1990s and foreground the role of Dalit activism.

Can you provide some suggestions for further readings?

I provide below a very select reading list, covering a range of topics:

Aloysius, G. Religion as Emancipatory Identity: A Buddhist Movement among the Tamils under Colonialism. New Delhi: New Age International Publishers, 1998.

Ambedkar, B.R. What Congress and Gandhi have done to the Untouchables? Bombay: Thacker & Co., Ltd., 1945.

Brueck, Laura. Writing Resistance. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Guru, Gopal, ed. Humiliation: Claims and Context. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Juergensmeyer, Mark. Religion as Social Vision: The Movement against Untouchability in Twentieth-Century Punjab. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

Mohan, P. Sanal. Modernity of Slavery: Struggles against Caste Inequality in Colonial Kerala. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Moon, Vasant. Growing Up Untouchable in India: A Dalit Autobiography. New York: Rowman &Littlefield Publishers, 2000. First published in Marathi as Vasti, 1995. Translated from the Marathi by Gail Omvedt.

Paik, Shailaja, Dalit Women’s Education in Modern India: Double Discrimination. Routledge, 2014.

Nagaraj, D. R. The Flaming Feet and Other Essays: The Dalit Movement in India. Prithvi Shobhi, ed. Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2011.

Rao, Anupama, ed. Gender and Caste. New Delhi: Kali for Women, 2003.

Rawat, Ramnarayan and Satyanarayana, K., eds. Dalit Studies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Rawat, Ramnarayan. Reconsidering Untouchability: Chamars and Dalit History in North India. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2011.

Rege, Sharmila. Writing Caste/ Writing Gender: Reading Dalit Women’s Testimonios. New Delhi: Zubaan, 2006.

Satyanarayana, K. and Tharu, Susie, eds. Steel Nibs are Sprouting: New Dalit Writing from South India (Dossier II). New Delhi: Harper Collins, 2013.

Ramnarayan Rawat teaches at the University of Delaware. He is currently completing a second book, “Parallel Publics: A History of Indian Democracy.” His recent co-edited book, Dalit Studies (2016), was published by Duke University Press.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Asia/Pacific Global History Religious History Social History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.