“You Will Never Get Anything Useful or of Value Out of This”

How a Difficult Diary Became My Dissertation

In a neat, ornate hand Katie Edwards wrote in her diary on April 4, 1870, about the new chapter in her life that awaited her in the Indian Territory. “After a good night rest in a clean bed I rose this morning much refreshed . . . started for the Mission . . . will start with 80 pupils,” she remarked. With this simple declaration Edwards left behind the security and comfort of Ohio and entered the intricate world of the Mvskoke and Seminole peoples in the Indian Territory. Arriving at the Presbyterian-run Tullahassee Mission, near present day Muskogee, Oklahoma, Edwards’s desire to be of service placed her in a Mvskoke/Seminole gestalt utterly foreign to her. From my initial reading of her diary, which runs from 1870–96, little could I know that Edwards’s 19th-century journey would consume my research life.

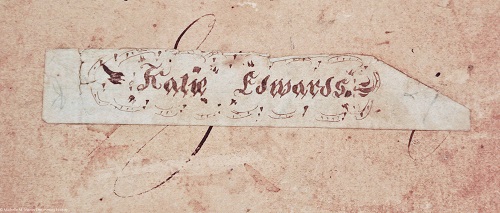

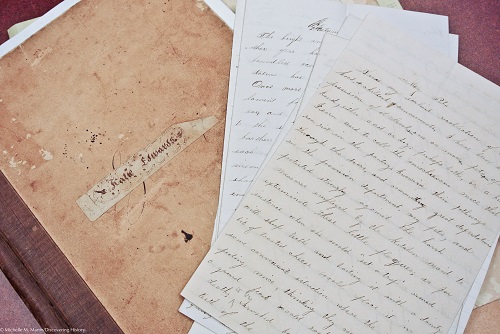

Katie Edwards’s diary at the Oklahoma History Center. Courtesy of the author

I discovered Edwards’s diary at the Oklahoma History Center’s research and archives division in Oklahoma City while searching for a woman’s 19th-century diary to create a one-woman living history program. As a public historian and practitioner of first-person living history interpretation, I wanted to portray a woman from the territorial period. As a historian the worst thing you can hear from an archivist is we don’t have anything that meets your research criteria. In my case the young archivist that assisted me emphatically declared this is the most miserable diary I have ever read, you will never get anything useful or of value out of this, trust me. Perhaps it was just curiosity or my refusal to accept that I could not find research material, but I cheerfully asked the archivist to bring me the entire series of boxes in the collection. When the five boxes arrived, I must admit that I was feeling dubious. How could five small archival boxes help me create a meaningful first-person interpretation? With white-gloved hands I opened the first box and took out the first folder. There on the cover the name Katie Edwards greeted me. Like a handshake across time, I felt compelled to at least look at the diaries.

After photographing the most delicate pages and requesting photocopies of additional diary materials, I returned home and voraciously read Edwards’s most intimate thoughts and private pain. Her diaries provided me with a focused account of one woman’s struggle to be accepted by her peers, find love, and make a life for herself in the Indian Territory, or so I thought. My initial reading of Edwards’s diary, written from her decidedly Anglo perspective, constituted a narrow view of not just her life but those of the many Mvskoke, African American, and multiethnic individuals she chronicled in her diary. At times the diary took on the trappings of a romance novel set against the backdrop of historical change for the Mvskoke and Seminole peoples and their indigenous neighbors. At the same time, however, Edwards’s anger toward the Mvskoke people, her mission colleagues, and her own family in Ohio perplexed me. I knew I would have to dig deeper into the diary to understand her world.

Katie Edwards’s diary at the Oklahoma History Center. Courtesy of the author

Quickly I realized that in one respect the archivist was indeed correct. Edwards’s diary is miserable, depressing, and at times hateful. For my original purpose of creating a living history program her diary is not suitable for audiences of all ages. As a matter of fact, if I were to create that one-woman program from her diary it would be more apropos as a Lifetime movie of the week. Soon the wall of my office became a huge flow chart with circles representing the various people Edwards writes of in her diary. Lines and dots connect them to one another. Kinship ties, marriages, births, deaths, and abandonments created a huge puzzle for me to unravel. After arriving at Tullahassee Mission Edwards ignored all advice and fell in love with one of her charges, a young Mvskoke/Seminole man named Douglas Bemo. By 1874, despite existing miscegenation laws, the couple married and embarked upon a life filled with hardship and sacrifice. From Edwards’s perspective she was the one suffering and sacrificing the most. On the other hand, Bemo devolved from her “darling boy,” her “beloved husband,” to a “vile Injun.” He was absent from Edwards’s diary in any meaningful, constructive way that would allow me as a historian to understand his role in the relationship. At this juncture my work reached a dead end.

A chance conversation with noted American Indian historian Donald L. Fixico, however, opened a new world of analytical possibilities for me. Instead of looking at Edwards’s diary and constructing a narrative from the Anglo perspective, why not view Edwards’s life from her husband’s cultural lens? By utilizing an indigenous-centered approach, perhaps I could create a portrait of an interracial couple and use their story as a vehicle to reassess American Indian-white relations in the 19th century on a personal level. Additionally, I could learn what life was like for Bemo as an indigenous man seemingly caught between the Mvskoke/Seminole and Anglo worlds. To achieve this indigenous assessment, I delved into Mvskoke and Seminole history and its varied facets that involve “experiencing the mental relationships between tangible and non-tangible things in the world and the universe” that permeate Mvskoke/Seminole ethos and reality.[1] Taking Edwards’s diary out of the Anglo historical/cultural context and shifting it into a Mvskoke/Seminole paradigm places the diary within what Mvskoke/Seminole people call Ibofanga, which is the “existence of all things and energy within all things.” Ibofanga unites the Mvskoke/Seminole people with the natural world, the worlds of those around them, and the spiritual realm and its energy.[2] This process of reexamining Edwards’s diary as a part of the Mvskoke/Seminole framework of Ibofanga constitutes the core of an indigenous methodology that Fixico calls the “Medicine Way.” Reinterpreting the reality of Edwards’s diary according to Mvskoke/Seminole principles, in which the physical and metaphysical worlds are constantly interconnected (unlike the Anglo world), shifts the diary from the realm of a home bound woman’s gendered, racialized narrative. Edwards’s diary, once reinterpreted, contains greater detail about the history and culture of the Mvskoke/Seminole people, and therefore her husband, than she ever intended or consciously realized.

With this approach, the deaths of Edwards and Bemo’s three children all at exactly 11 months of age of the same affliction becomes more than mere coincidence. While the burial of the three deceased infants in the couple’s yard comforts Edwards, the conjoining of the worlds of the living and dead in close proximity spells spiritual disaster for Bemo. The wild shrieking at a “camp meeting” under a canopy of trees that Edwards and Bemo attend signifies a Mvskoke traditional stomp dance and not an abomination of Christian tradition. Where desperation, despair, and one-sided narrative once shaped my perspective, with a fresh set of eyes and an indigenous-centered approach each page of Edwards’s diary springs forth pregnant with analytical possibility. Edwards’s diary, while not useful for me as a living history interpreter, quickly reframed the focus of my doctoral studies. As a scholar, my willingness to adapt and accept new methodological tools that embrace indigeneity allowed me to delve deeper into an Anglo narrative source seeking the hidden indigenous voice contained in its pages. This analytical process transformed a difficult, angry woman’s diary into a useful tool that I could use to reevaluate the nature of American Indian-white interpersonal relations. Equal parts love story and clash of cultures, Edwards’s diary constitutes a rich source that now forms the focus of my dissertation. Far from being of no value, this problematic diary is a doorway into the past that is too enticing to simply walk away from. Love, hatred, jealousy, sex, and death are cultural universals that unite humans across time. Edwards and Bemo’s lives possess all of these in abundance and more.

Michelle M. Martin is a doctoral student at the University of New Mexico and studies the intersection of gender, race, and ethnicity in the 19th-century American West. Her work focuses on the complex web of relationships between Mvskoke (Muscogee), Seminole, Anglo, and African American peoples that lived in the Indian Territory from 1840–1906.

Michelle M. Martin is a doctoral student at the University of New Mexico and studies the intersection of gender, race, and ethnicity in the 19th-century American West. Her work focuses on the complex web of relationships between Mvskoke (Muscogee), Seminole, Anglo, and African American peoples that lived in the Indian Territory from 1840–1906.

[1] Donald L. Fixico. American Indian Mind in a Linear World: American Indian Studies and Traditional Knowledge (New York, London: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2009), 3.

[2] Fixico. American Indian Mind in a Linear World.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Resources for Graduate Students Archives Thematic Indigenous History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.