An Asian American attorney contacted me recently to ask whether I knew that Denver once had a Chinatown. He expressed dismay that this historical fact was not widely known. There should be, at the very least, a sign to commemorate it, he said. It turns out he had called the right person—I did know that there was a Chinatown in Denver and I had even written articles about it.

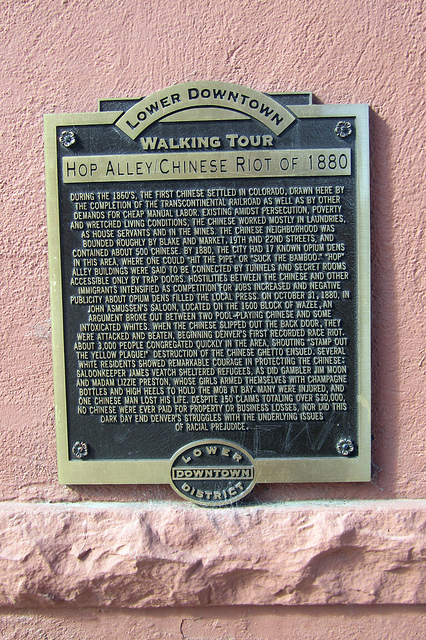

Historical marker commemorating the 1880 anti-Chinese riot in Denver. Wally Gobetz/via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

I told him about a historic marker with the somewhat misleading title “Hop Alley/Chinese Riot of 1880” located on the side of a building on 20th Street, between Blake and Market Streets in Lower Downtown Denver. While sympathetic to the persecuted Chinese, the marker is less about them and their community and more about how some of them were saved by some courageous Denverites, especially those belonging to the city’s demimonde, during a violent rampage on October 31, 1880, that nearly destroyed Chinatown. It was the city’s first race riot and one of the worst anti-Chinese incidents in the American West. Still, the Chinese remained to rebuild their community. Eventually their population dwindled because of further anti-Chinese violence and racist laws that prevented them from replenishing their numbers through immigration and reproduction.

Not a lot of people are aware that Denver’s Chinatown ever existed or that there were in fact many Chinatowns—ghettos really—throughout the American West. During the latter half of the 19th century, Chinese immigrants were an integral part of communities in the region and contributed to the development of its economy until they were driven out. As you would expect from race-based pogroms, their homes were destroyed and they were expelled from the West. “Not a Chinaman’s Chance” is an expression from the period that succinctly describes their position as one of America’s vulnerable minorities. With the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Chinese population in America declined dramatically and would have disappeared altogether, which was the law’s intent, if not for its repeal in 1943 and the passage of the Hart-Celler Act of 1965 that allowed immigrants from China to come to the United States in numbers equal to other immigrant groups. Now Chinese Americans are the largest Asian American group in Denver and in the country, and Asian Americans in general are the country’s fastest growing immigrant group.

There were other Asians in Denver too. Japanese immigrants arrived during the Gilded Age and settled adjacent to Denver’s Chinese community. Like the immigrants from China, they came to work to support their families and suffered from prejudice and discrimination. Eventually, they too were excluded from the country beginning with the secret Gentlemen’s Agreement in 1907 that resulted in the Japanese government denying them passports to travel to the United States, and the enactment of the Immigration Act of 1924 that kept them out of America. Fortunately, they were able to establish families in the United States and produce a second generation—the Nisei. The Nisei, like other young Asian Americans who served in the US military, fought the country’s Axis enemies while having to cope with the country’s racist policies toward them at the same time. Many of the Nisei left for the American military straight out of one of the 10 concentration camps where the government had imprisoned them and their families for no other reason than their race. One of them was the Amache concentration camp in southeast Colorado near the Kansas border. Among the prisoners who left Amache to serve in the US Army was Kiyoshi K. Muranaga, who was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for heroism while fighting in Italy.

Ironically, Denver’s Japanese American population actually grew after World War II when the Amache inmates decided to stay in the state after release. Many moved to Denver. They did so because they knew that they would not be welcomed back home on the West Coast and decided to make a new home for themselves in the Centennial State where Ralph L. Carr, former governor of Colorado, had welcomed them. Unlike most of the politicians of his day, Carr was a profile in courage for supporting the Japanese Americans whose civil rights were grossly violated. A bust of Carr can be found at Sakura Square, a small shopping plaza located at the intersection of 19th Street and Larimer Street. It is one of the tiniest of the Asian American enclaves that have emerged in Denver.

Since the 1960s, Denver’s Asian American population has grown and become far more diverse. According to the 2010 decennial census, in the order of population size Colorado’s six largest Asian ethnic groups are Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans, Asian Indians, Filipinos, and Japanese. They have helped make Denver and Colorado part of the global economy.

Explore Asian American history at the 2017 annual meeting! Here is a glance at some of the sessions and papers of interest:

Deconstructing Hemispheric Orientalism: Exploring Alternative Anti-Asian Discourses across the Americas

AHA Session 68

Immigration and Ethnic History Society 1

Friday, January 6, 2017, 8:30–10:00 a.m.

Colorado Convention Center, Room 401

Chair: Cindy I-Fen Cheng, University of Wisconsin–Madison

Papers:

Foreign: Deconstructing Chinese Jamaican Transnational Identity Formation and Negotiations of Authenticity

Jordan Lynton, Indiana University

Comparative Orientalisms in the Americas: Race Patriots and Indigeneity in 20th-Century Mexico and El Salvador

Jason Oliver Chang, University of Connecticut at Storrs

Southeast Asian Refugees in Argentina after the Vietnam War, 1979–85

Sam Vong, University of Texas at Austin

Memories of War and Trauma and the Rise of Postcolonial Activism: Migrant/Minority Communities in Asia and America

AHA Session 101

Immigration and Ethnic History Society 2

Friday, January 6, 2017, 10:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

Hyatt Regency Denver, Centennial Ballroom A

Chair: Judy T. Wu, University of California, Irvine

Papers:

He Said, She Said: Uncovering Family Trauma through Oral History in New Mexico’s Land-Grant Movement

Lorena Oropeza, University of California, Davis

“Hiroshima Nagasaki Indochina: Unite to Oppose the Genocide of Asian People”: Linking Memory and Activism in Asian American Citizenship

Naoko Wake, Michigan State University

Memory, Activism, and the Korean War: Korean American Construction of an Integrated Self

Ji-Yeon Yuh, Northwestern University

Resident Memory, Resonant Trauma: Incidental Migration and Long-Term Antiwar Protest on South Korea’s Jeju Island

Nan Kim, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

William Wei, professor of history at the University of Colorado Boulder, is the author of Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State (Univ. of Washington Press, 2016).

Tags: AHA Today 2017 Annual Meeting Asian American and Pacific Islander History Migration/Immigration/Diaspora

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.