Jessica and Tiffany

While attending the AHA’s 2016 annual meeting, Jessica and I—PhD candidates in history at Binghamton University in New York—had a revelation of sorts at the Graduate and Early Career Committee’s open forum on Career Diversity. Like many other history graduate students, we had accepted the “Plan A” culture that exists in so many institutions: “Plan A” is a tenure-track job in academia; “Plan B” is whatever we can do to avoid becoming baristas with PhDs. We were thrilled—and a little shocked—to discover the high percentage of history doctorates who successfully use their degree outside of the professoriate. According to an AHA report, almost 25 percent of history PhDs find employment outside of academia. We were also happy to discover that we had been making the right choices in graduate school to prepare us for what the AHA calls “Career Diversity”—jobs both within and outside of academia. Here we share our experiences as an example, but with the understanding that preparation depends on individual and personal initiative and interests. Although the institutionalized “Plan A” versus “Plan B” culture does not encourage us to do so, we can define the purpose of our own graduate educations and intentionally cultivate a range of skills applicable to a diversity of careers.

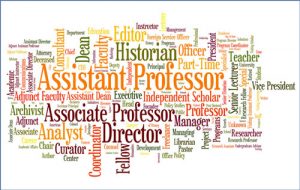

A visualization of job titles for 2,500 history PhDs who graduated between 1998 and 2009. From “The Many Careers of History PhDs: A Study of Job Outcomes, Spring 2013.”

Although opportunities for graduate employment beyond teaching assistantships vary greatly among colleges and universities, both of us found such opportunities within our institutions. We had already been teaching for a number of years, and decided to seek alternative graduate employment opportunities with the hopes of diversifying our experiences and skills.

Jessica

Initially I hesitated about stepping away from the familiarity of working as a teaching assistant; after three years, I felt comfortable with public speaking, assessing and offering feedback on others’ work, and mentoring students. Driven by the desire for a more varied education, I transitioned into the role of graduate research director at the Center for the Historical Study of Women and Gender. In my two years in that role the abilities I acquired as a teaching assistant evolved and broadened in innumerable ways: my technological literacy improved as I learned new programs. Working in a more collaborative environment that involved advanced faculty, undergraduate students, and scholars outside the university allowed me to enhance the communication skills I had already acquired while teaching.

Tiffany

I stepped away from the classroom to serve as one of the managing editors of the Journal of Women’s History to explore a history career outside of the classroom. After two years as managing editor, I can point to an impressive array of skills gained. My writing and editing skills have improved as I copyedit and proof articles that appear in the journal. This has made me a better editor and a better writer. I broadened my communication skills by frequently corresponding with authors. I have also become an expert on the process of producing a high-level academic journal, expanding my skillset beyond the classroom and into the more professional side of history.

Jessica and Tiffany

When searching for paid opportunities outside of teaching assistantships—and since only approximately 40 percent of graduate students get such assistantships, most graduate students will have to do this—do not be afraid to look for positions that develop different skill sets. Look for research centers that are associated or even loosely affiliated with your department, research assistantships (sometimes with individual faculty members), and jobs within academic and student affairs. These positions will likely allow you to cultivate the skills you already have, while forcing you to think and work in new ways.

Opportunities to expand our skills, experiences, and knowledge base also exist beyond our home institutions. Last year, for example, we helped plan and coordinate academic conferences. We quickly learned the behind-the-scenes work that it takes to organize a conference: announcing the call for papers, collecting and reviewing applications, setting up official websites and Twitter handles, reserving blocks of hotel rooms, suggesting local services for attendees, and anticipating day-of needs. Collaborating with scholars and local businesses to develop this event allowed us to use some of the skills we had acquired in the classroom—time management, multitasking, and communication—and apply them in a practical and public way.

Ultimately, we believe that it is vital for history graduate students to seek out opportunities and experiences that take us beyond the classroom. It is easy upon entering academia to forget the passion that led us there and to become consumed by “Plan A,” “Plan B,” and the employment challenges for our field. Pushing ourselves to step beyond the graduate seminar and our roles as teaching assistants has allowed us to mitigate against the culture of “Plan A” in two key ways: we have nurtured skills, habits, and ideas that translate to a more diverse curriculum vita for both the academic and nonacademic job markets; and we are reminded of the multiple ways we can embrace history (from digital projects to publishing) and the passion that brought us to graduate school in the first place. Though it never feels like there is enough time and department support, these alternative experiences that prime us for career diversity are available—even if, at times, they are unpaid. Think carefully about the skills you want to obtain, the paths you want to take after graduate school—both academic and nonacademic—and then purposely and thoughtfully pursue opportunities that will help you reach those goals. Reach out to local museums, historical societies, professional organizations, and digital history projects to ask if you can become involved. Attending the 2016 AHA annual meeting made me, Jessica, realize that I want to learn more about digital history; I contacted the creators of an online digital history project and am now beginning work as their graduate intern. Even if the culture of our field is slow to move away from the culture of “Plan A” versus “Plan B,” we can act under our own initiative to prepare ourselves for a career in this field that we love so much.

Editor’s Note: For a listing of professional development and career resources at the 2017 annual meeting in Denver, please visit Perspectives on History.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Jessica Derleth is a US historian whose research focuses on how American suffragists used gender as a political strategy to advance their cause. Derleth’s research interests and presentations include gender roles and performance; food history; social movements, especially women’s activism; and the history of sexuality, gender, and empire.

Tiffany Baugh-Helton is a PhD candidate in history at Binghamton University in New York. She is in the final stages of editing her dissertation, “We Didn’t Know We Were Making History: The UAW Women’s Auxiliaries in Great Depression and World War II Era Detroit.” She currently lives in Detroit.

Tags: AHA Today Career Diversity for Historians Resources for Graduate Students Graduate Education

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.