Last fall, Virginia Tech students taking History 3604: Russia to Peter the Great engaged in a sustained discussion on “why study history?” In the class, we often took examples from current news or recent history and established connections to the historical period covered by the readings, lecture, and assignments (here’s a link to the syllabus). Each week, a group of two or three students wrote a short statement explaining how the readings illustrated the value of studying history, which we then discussed in class. Finally, at the end of the semester, the entire class collaborated on this essay, which synthesizes those weekly contributions into a reflection on why studying the history of Russia to Peter the Great is intrinsically and instrumentally valuable.

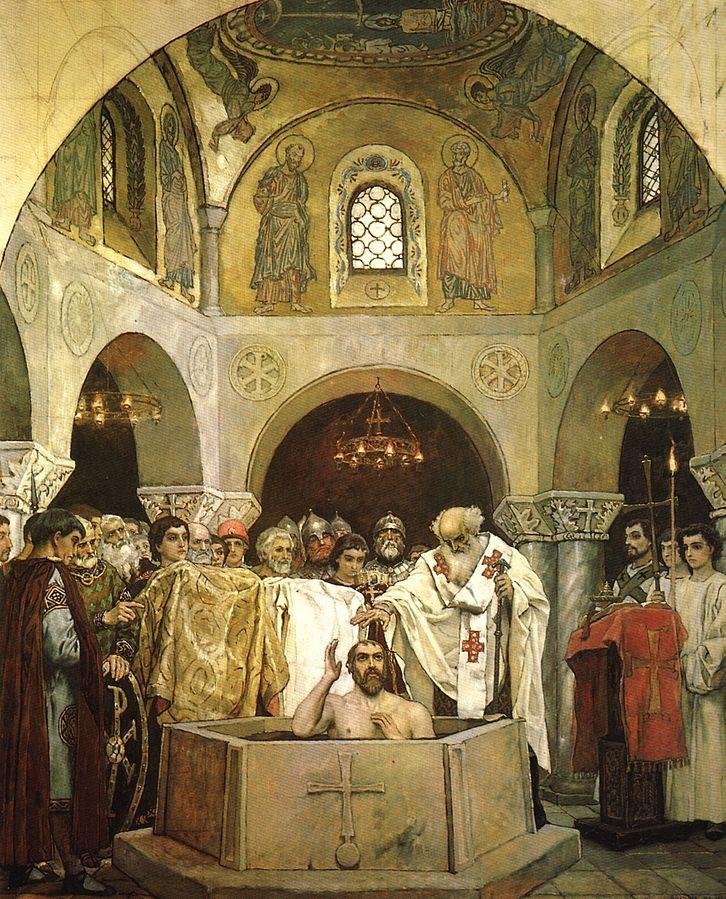

Illustration 1: Baptism of Russia, painted by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1890. Wikimedia Commons

Studying Russian history from its founding in the ninth century until the beginning of the era of Peter the Great in the late 17th century illustrates how this emerging nation-state navigated complex processes such as building a national political order, sustaining an evolving cultural identity, and legitimizing power through personality, rituals, and institutions. Studying these processes in a historical context—distant in terms of both time and location—provides insights into similar patterns in the more recent past, the present, and into the future, thus demonstrating why history matters.

This course on early Russian history, for example, helped students appreciate the complex relationships that exist between cultures that share the same geographical space. Russia was created in the ninth century when indigenous Slavic communities gradually integrated with the Scandinavian ruling elite. Since then, Russian history has been characterized by tensions between internal cohesion and external threats. This is most obvious during the 14th and the 15th centuries, when Mongol rule threatened the very existence of the Russian political system. At the same time, this era witnessed the consolidation of power by Moscow’s princes, political collaboration between church and state, and creation of a foundation for the steady expansion of boundaries under the Russian autocratic state of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Illustration 2: Church Schism, painted by Vasilii Surokov, 1886. Wikimedia Commons

The course also allowed students to acquire insights into the formation of Russian national identity. Geographical location enabled, and indeed compelled, Russians to interact with neighboring states, peoples, and cultures on all sides in ways that shaped formal customs, influenced spiritual values, and guided cultural practices. Over the centuries, for example, the Orthodox Church contributed to a growing sense of cultural identity among the Russian population while also defining boundaries with adjoining cultures, peoples, and states. In the 17th century, the church’s role in fostering national unity during the Time of Troubles, when Russia was invaded by foreign armies, was followed by a schism that divided the nation, communities, and even families (illustration 2).

Illustration 3: Ivan IV and the oprichniki, by Nikolai Nevrev, painted in the 1870s. Wikimedia Commons

The evolving role of political leaders from the founding of the Russian state through the Mongol era and into the early modern period also provides evidence of the legitimization of power through personality, rituals, and institutions. The conversion of Russia to Christianity under Vladimir (ruled 980–1015) (illustration 1), the legal codes introduced by Iaroslav (ruled 1019–54), the military campaigns of Vladimir Monomak (ruled 1113–25), and the national reconciliation under Mikhail (ruled 1613–45) are examples of political leadership that undermine simplistic claims of immutable or inevitable autocracy in Russia. The reign of Ivan the Terrible—a central topic of this course—provides a clear example of how a nuanced approach to history matters. Ivan IV (ruled 1547–84) successfully expanded Russia’s borders, consolidated personal power, and strengthened the state (illustration 3). At the same time, his capricious actions, arbitrary methods, and personal ambitions caused numerous deaths, contributed to economic collapse, and put the survival of Russia in jeopardy. Exploring the actual exercise of power within changing contexts provided students with skills for examining the dynamics of political action and reaction in more recent contexts, including the most obvious current example, the presidency of Vladimir Putin. Throughout the semester, the class discussed how Putin’s use of political symbolism, his reliance on a network of loyalists, and his efforts to position Russia between Europe and Asia were connected to specific themes from earlier periods of Russian history.

Studying history is not just about collecting facts—instead, it is a process of acquiring, mastering, and analyzing layered and nuanced information on many subjects. The value of history thus lies in the ability to identify, process, and synthesize potentially overlooked details to explain a broader idea, culture, or event. Teaching history in reference to current examples is also a powerful reminder of how an unexpected historical turn can change perceptions. On September 6, when the topic was the role of warrior princes in the first centuries of Russian history, the class began with a discussion of several well-known images of Putin engaged in traditionally masculine activities such as hunting, fishing, and horseback riding. In the following class, September 8, this question of images of political strength was further illustrated with a widely circulated photograph of President Obama and President Putin engaged in what appeared to be a tense exchange at the G20 meeting in China. It was only three months later that we learned that this exchange was the moment when Obama confronted Putin with accusations about hacking the Democratic National Committee. For historians, even the most recent past is subject to revision, as new knowledge is disclosed in ways that change interpretations of historical events. This willingness to think critically and creatively about the past is the most valuable lesson that students can learn from repeatedly asking the question: why does history matter?

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

E Thomas Ewing is professor history and associate dean of graduate studies and research in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences at Virginia Tech. This essay was co-authored by his students enrolled in HIST 3604: Russia to Peter the Great.

Tags: AHA Today Asia/Pacific Europe Global History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.