AHA Today , Current Events in Historical Context , From the National History Center

Writing the Cold War Back In: How History Influences Chinese Foreign Policy

As Sino-American relations have emerged as a critical foreign policy issue in the Trump administration, public discourse has been awash with many all too familiar and ill-informed narratives about China and its global objectives. Often, these narratives are derived from overly simplistic views of how China’s past affects the present. Policymakers and journalists have been obsessed with the idea that the People’s Republic of China is trying to reconstruct the “tributary system” or “Sinocentric order” that governed its relations with its neighbors before the 19th century. One former CIA analyst explained recently in the Washington Examiner that China “is now working to resurrect a 21st century version of its ‘lost’ Southeast Asian tributary system.” Secretary of Defense James Mattis is reported to have made similar remarks during his visit to Asia in February. The trouble with such claims is that they grossly oversimplify Chinese policy and completely ignore the problems that historians have raised with the very notion of a “tributary system.”

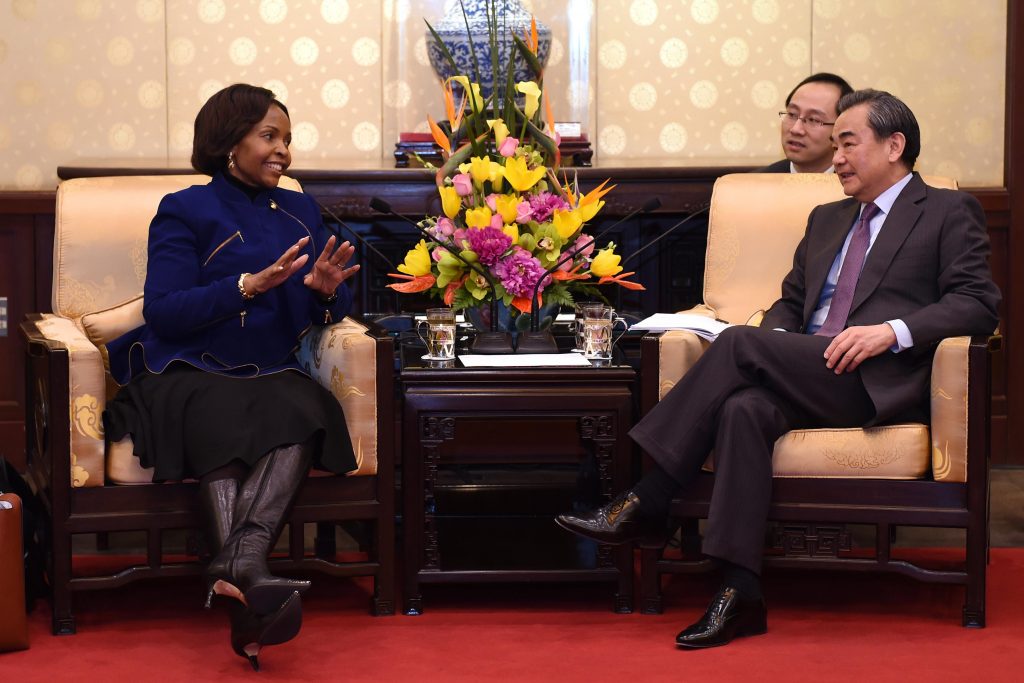

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets with Minister of International Relations Maite Nkoana-Mashabane at a South Africa-China bilateral meeting in February 2017. GovernmentZA via Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

While pundits make dubious connections between Beijing’s current ambitions and those of Dynastic China, they spend curiously little time discussing Chinese Cold War foreign policy. Yet the diplomacy of this less distant era, which aimed to build an alternative to the superpower-dominated world order by focusing on other Afro-Asian countries, is often more germane to understanding contemporary Chinese diplomacy. The bizarre disparity in coverage reflects an Orientalist bias toward explaining everything about Asia as a byproduct of an ancient and unchanging traditional culture.

During my talk at the Washington History Seminar, I discussed my recent book Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry during the Cold War (2017). I explained how the availability of new Chinese archival materials from the 1950s and 1960s has enabled historians to arrive at a more detailed and more nuanced understanding of Beijing’s foreign policy during this period. And I talked about how some of the key concerns that drove China’s Cold War foreign policy continue to inform its approach to world affairs and influence its relations with Asian and African countries.

I was fortunate that the time I spent researching and writing my book corresponded with a period of relative archival openness in China. Between 2005 and 2009, the PRC foreign ministry released several accessions of its foreign policy files covering the period from 1949 to 1965 before reclassifying many of them in 2012. I was part of a group of scholars, including Lorenz Lüthi, Jeremy Friedman, Austin Jersild, and Sulmaan Khan, who drew on these materials to shed new light on the PRC’s diplomatic history. One thing that these materials made clear was that the scope of Chinese activities in newly independent Asian and African countries was greater than historians had previously surmised.

When the Chinese Communist Party first launched its campaign to gain power over the Chinese mainland during the 1920s, it viewed its revolution as part of a much broader global struggle against imperialism—a struggle in which China needed to play an important role. During the Cold War, the PRC saw itself as a model of postcolonial nation building that newly independent countries in Asia and Africa could emulate. Its leaders believed they had something to offer Afro-Asian nations politically and morally that the West lacked. The objective of Chinese leaders was to create a radicalized community of Afro-Asian nations that helped each other gain self-sufficiency while opposing American and Soviet power. While this agenda was not without connection to dynastic China’s long history as the cultural and economic center of Asia, it more directly reflected the logic of the Cold War era. It sought to counter US-led efforts to isolate China in the name of containing communism while playing on the rising anticolonial sentiments that sprung from the decolonization of the Global South.

Current Chinese foreign policy in Asia and Africa reflects a broad array of historical influences, but it cannot be understood without reference to the Cold War. Beijing’s rhetoric about “win-win” cooperation through which both China and its neighbors can flourish is highly similar to its emphasis on mutually beneficial aid during the 1960s. China’s most important political leaders have at times very directly invoked the diplomacy of their Cold War era predecessors as a basis for current policy. During his first visit to Africa, President Xi Jinping made it clear that he was continuing what had been started by Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. He praised the CCP’s most well-known statesmen for creating a “fraternal bond” with African countries and ushering in “a new epoch in Africa-China relations.”

But the linkages between Cold War Chinese foreign policy and Beijing’s current efforts to expand its influence in Asia and Africa have been largely missed by the media and inside the beltway China experts. Even the most knowledgeable journalists have understated the relevance of the Cold War. John Pomfret’s recent book, The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom (2016), covers over 200 years of Sino-American relations with great depth and flair but devotes only a few brief chapters to Cold War era rivalry. China’s activism in the Third World and its impact on relations with the United States are barely touched upon. Similarly, Howard French’s Everything under the Heavens (2017) insightfully probes “how the past helps shape China’s push for Global Power.” Yet the Cold War only figures marginally in his narrative of how past eras influence contemporary Chinese diplomacy.

Historians have an important role to play in revising mainstream views of China and its role in the world. The media and many of the so-called China experts working in the government and think tanks have written the Cold War out of prevailing explanations of Chinese foreign policy. It must be the task of the historian to write it back in.

Established by the AHA in 2002, the National History Center brings historians into conversations with policymakers and other leaders to stress the importance of historical perspectives in public decision-making. Today’s author, Gregg Brazinsky, recently presented in the NHC’s Washington History Seminar program on “Winning the Third World: Sino-American Competition during the Cold War.”

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Gregg Brazinsky is an associate professor of history and international affairs at the George Washington University. In addition to Winning the Third World, he is also the author of Nation Building in South Korea: Koreans, Americans, and the Making of a Democracy. His next project explores Sino-North Korean relations. Follow him on Twitter @GBrazinsky.

Tags: AHA Today Current Events in Historical Context From the National History Center Asia/Pacific Political History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.