“Dogs were our defenders! For black men who didn’t have guns . . .”

A. Christiaan (interview, January 18, 2016)

In May 1922, the Bondelswarts (a Nama nation in southern Namibia) took up arms against the South African colonial administration.[1] The short-lived and poorly organized uprising was put down with ground troops, machine guns, and airplane bombing of the reserve. Prior to the uprising, the Nama constantly complained over a tax on dog ownership that was introduced into the rural areas in 1917.

Students of African history are familiar with conflict over hut and poll taxes. But a tax on dogs? That seemed oddly specific to me to be a major cause of armed revolt. I had to dig deeper to understand why this was the case. This post will explore the history of dogs in southern Namibia to illuminate the severity of this tax, and to hint at some of the difficulties in reconstructing what Sandra Swart has termed “animal-sensitive history.”

Canis Mesomelas. Sketched by Robert Jacob Gordon, visitor to the Cape 1777–95. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam (www.robertjacobgordon.nl)

In precolonial times, sheep pastoralism was key to the economies of the indigenous Nama in southern Namibia. Nations such as the Bondelswarts engaged in circular migration between Namibia and the Northern Cape, following sparse rainfall, grazing, and ephemeral rivers. Beyond the oft-feared frontier stock raiders and armed colonial commando troops, sheep farmers faced enemies, particularly the jackal (Canis Mesomelas). The onset of settler colonialism in southern Africa had led to the decimation of apex predators such as lions and hyena because of the threat they posed to cattle production. This allowed jackals, who have shorter gestation periods and variable diets, to rise up the food chain—a process known as “meso-predator release.”[2] Importantly, the rise in jackal population became concentrated in sheep-farming regions. As sheep numbers grew, jackals adapted their diets and pursued slow-moving livestock instead of ever-dwindling game and less satisfying rodents.

In protecting their livestock, the Nama had to innovate. Firearms (mostly matchlock muskets) were expensive and unreliable; instead, many Nama engaged in rigorous dog breeding and training as a defensive form of vermin control. In these districts, the Nama found sighthounds (lurchers) to be far more useful than scent-hounds: the flat, dry expanses make it easy to spot vermin from a distance, but the low humidity and high evaporation make it difficult for dogs to follow a scent for too long.

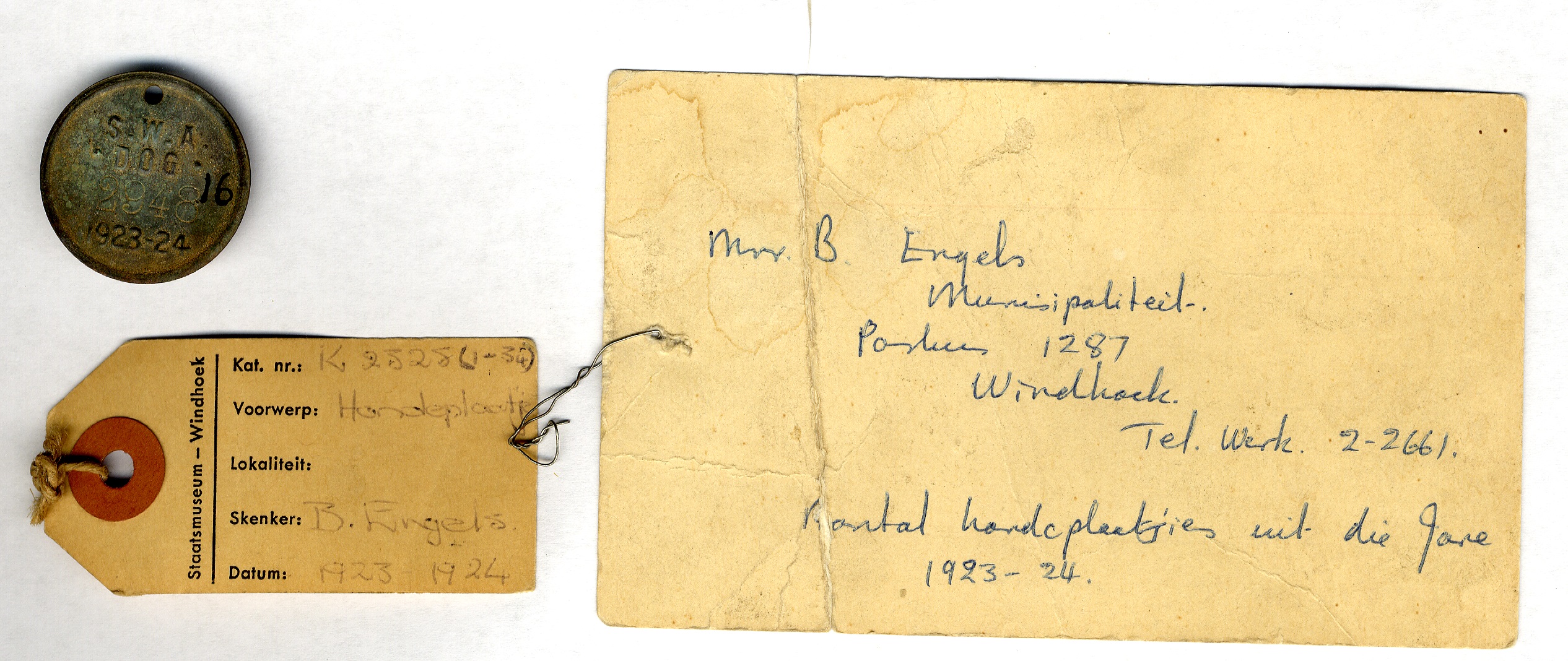

Dog Licence Badge, 1923–24. Courtesy of the National Archives of Namibia: Artifacts Ephemera Collection, ATF A.0839_X035

Dogs were trained using scents, but the scent was generally of the shepherd or his flock. Dogs were given sheep’s milk to drink, or fed some dried meat that the shepherd had been carrying in his veldskoene (rawhide shoes) for some time. The Nama even built trust by applying armpit sweat directly to the dog’s nostrils. Loyalty was key, as the fate of the flock was at stake. In conversation with several Bondelswarts families, I learned that shepherds kept at least two dogs each, one male and one female, as many Nama feared that if a female jackal was in heat and approached the sheep, a male dog would not kill it or chase it away.

The process of killing predators such as jackals was observed by many travelers to precolonial Namibia, including Gustav de Vylder, a Swedish naturalist who participated in several hunts with the Nama. He observed that when predators approached the kraal (protective corral of bush wattle), a line of dogs would be strung out across the veld. The Nama would then walk toward the predator until the dogs had encircled the creature and eliminated it. Beyond killing jackals for pastoral production purposes, their pelts could be sold to the Cape trade, and jackal meat was considered a delicacy. This was a defensive arrangement, however. While the Nama did occasionally go jackal hunting with their dogs, they were far more likely to keep the dogs with the flock for local protection.

Dog ownership became even more important as colonial settlement increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After the 1904–07 genocide by the Germans, migratory pastoralism became increasingly difficult as large portions of Nama land were seized by former soldiers turned settlers. Furthermore, colonial laws forbade all but the kaptein (Nama headman) from owning firearms. Dogs became a precious resource for embattled pastoralists seeking to avoid poorly paid wage work on settler farms. Against these odds, many Nama successfully maintained subsistence pastoralist production, exacerbating labor shortages on heavily subsidized white farms.

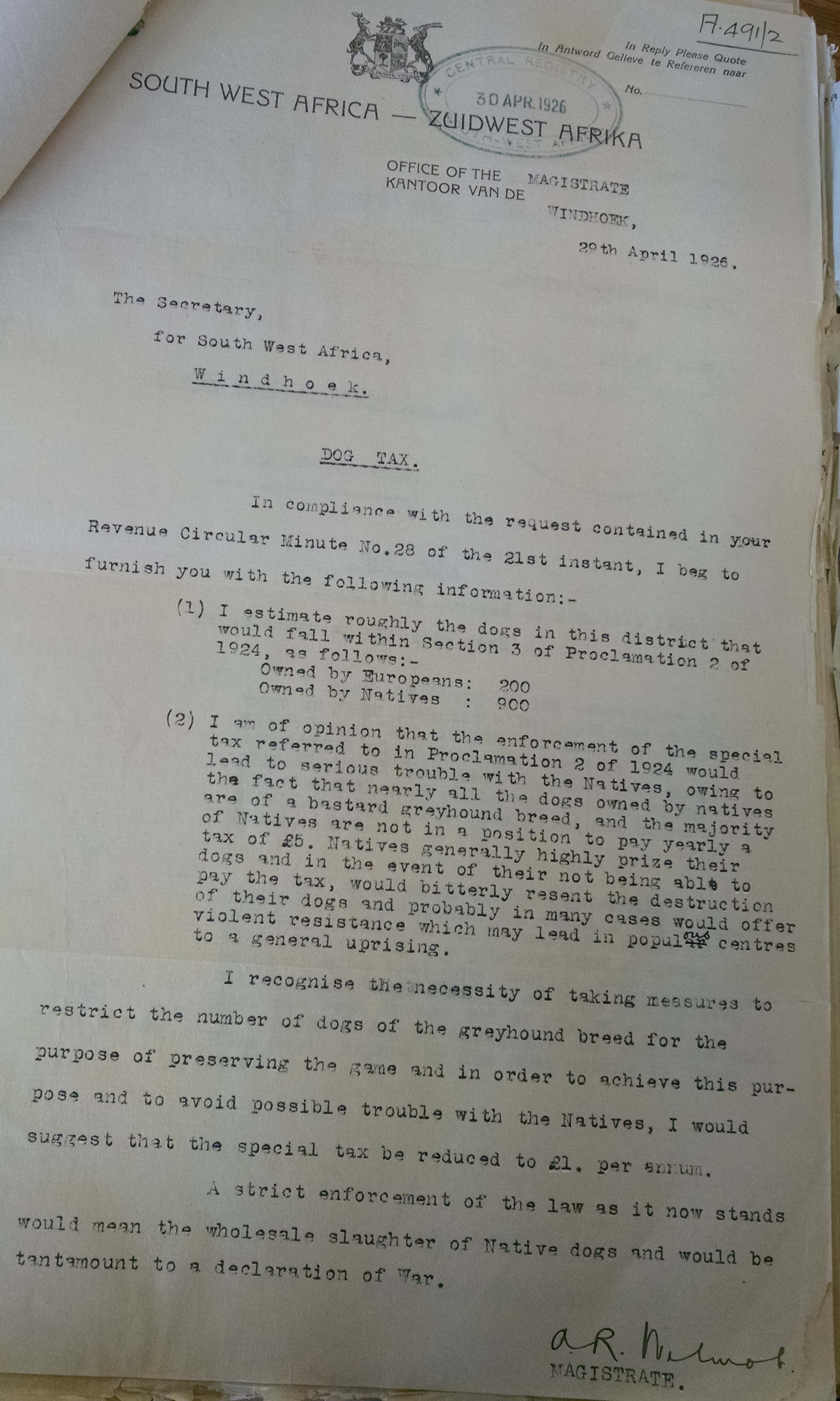

Correspondence between the Windhoek Magistrate and the Secretary for SWA in 1926, noting that slaughter of African-owned dogs could be “tantamount to a declaration of war.” National Archives of Namibia SWAA A.491/2 (v.1)

Enter the dog tax. Every year from 1917, both white and black Namibians were required to purchase a licence for each dog they owned.[3] Those caught refusing or unable to pay the tax were fined, and their dogs killed if the balance was not settled within the week. It was routine for more dogs to be killed than those registered and licensed. In 1917 alone, at least 2,830 African-owned dogs were killed. The racialized enforcement was clear; the European-owned number was only 135.

For many Bondelswarts, the tax was impossible to pay. Average wages in 1921—when the tax was £1 per dog per annum—were between 15 shillings and £1 and 10 shillings per month.[4] Those not formally employed had to sell livestock or labor for cash, and many felt that the systematic collection in the Bondelswarts reserve revealed that the tax was being used to address labor shortages.[5]

Gijs Hofmeyr, the administrator for the Namibian mandate, admitted as such. In 1923, he stated that the dog tax was necessary to incentivize the Bondelswarts to take up “honest labour,” which he conceived only as wage labor on white-owned farms. Hofmeyr and the colonial administration were ignorant of the nature of the Nama pastoral economy, believing that dogs were solely used for hunting game, and therefore providing subsistence for the people. Most scholarship on the Bondelswarts uprising has followed this analysis, looking at the dog tax as a closure of hunting commons. My research, however, reveals that the tax didn’t affect game hunting much—it was already marginal at that time—rather, it weakened the Nama’s pastoral production system by making it costly to own hounds. In a sense, the dog tax provided a subsidy for poor white farmers struggling to compete with black pastoralists or obtain laborers.

Bondelswarts homestead at |Guruxas, where the South Africans bombed in 1922. Photo by Bernard C. Moore

Reconstructing the economic role of man’s best friend in Namibia is not always an easy process, and it necessitates critical engagement with precolonial traveler’s accounts, publications and papers of volkekundiges (colonial/apartheid ethnologists), veterinary and agricultural reports and research, not to mention mountains of administrative correspondence with magistrates and local farmers. As Susan Nance has written, “Animals are everywhere, and there has never been a purely human moment in world history.” Whether they were dogs, vermin, or sheep, these animals were present throughout history, but we only tend to find them lurking at the margins of this documentation. Even if we are writing about decidedly anthropocentric topics like agricultural production and conflicts over farm labor and proletarianization, we must try to locate the nonhuman in “animal-sensitive histories” to reveal points of friction that would otherwise go unnoticed. In this sense, a dog tax could affect sheep, jackals, and shepherds just as much as canines.

It’s difficult to ascertain exactly how many Nama entered wage labor directly because of the dog tax alone. The tax, however, provides an interesting insight into proletarianization during this era. Dogs were seen by the Nama as a form of agricultural technology, or, in Marxist terms, dogs were part of the productive forces. Targeting dogs, then, challenged sheep pastoralism. In my next post, I will explore the ways in which vermin extermination intensified in subsequent decades.

[1] After World War I and the stripping of Germany’s colonies, Namibia became a Class-C League of Nations mandate under administration of its neighbor, South Africa. Settler colonial policies were quickly put in place.

[2] Similar observations have been made regarding coyotes in the American West.

[3] This licence had no veterinary aspects or requirements; it merely meant that the dog was owned and alive, and that payment was made.

[4] Twenty shillings to the South African pound.

[5] Of these wages, a large percentage was paid in kind as well, such as work-for-grazing arrangements, reducing the possibility to accrue savings for taxation purposes.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Perspectives Summer Columns Africa Environmental History Indigenous History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.