“Vermin are Like Weeds in Your Garden”: Fences, Poisons, and Agricultural Transformation in Colonial Namibia

“Ongediertes is soos onkruid in jou tuin. Elke jaar moet jy weer van nuuts af begin skoonmaak.”[Vermin are like weeds in your garden. Each year you must start cleaning from scratch.] —Malcolm Allison, US Fish and Wildlife Service, 1961

If the 1920s in southern Namibia featured violent colonial interventions to facilitate the transfer of black pastoralists’ land and labor to white ranchers, the 1930s–60s were a time of consolidation of white capitalist agriculture—to make it stable, profitable, and “modern.” In Namibia, and southern Africa broadly, “modern” agriculture was often conceived of as technologically innovative, leading to increased outputs. This intensification and application of new technology can be observed in vermin control.

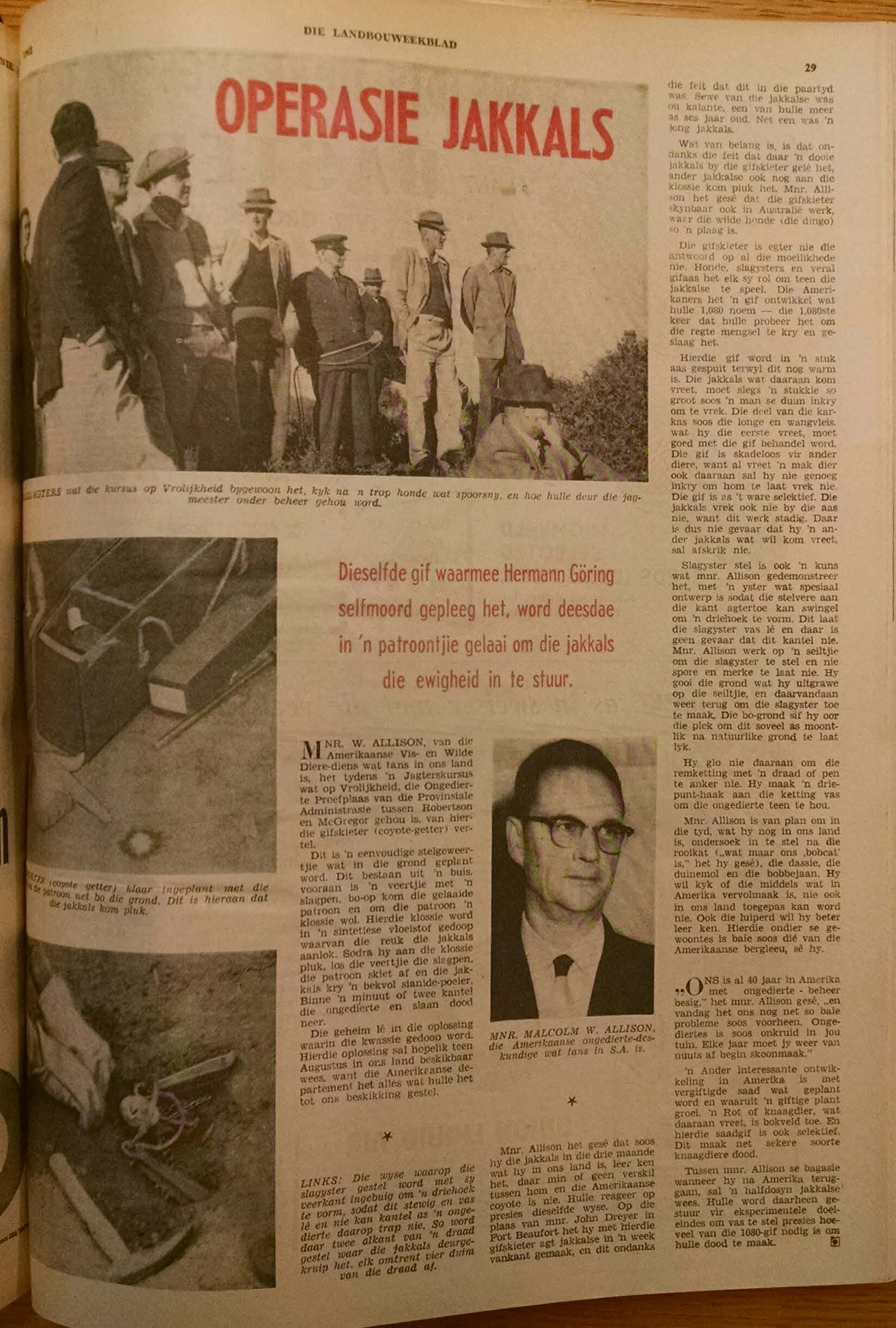

Newspaper article documenting the US Fish & Wildlife Service’s Malcolm Allison’s trip to South Africa. (Die Landbouweekblad, June 13, 1961)

While visiting the National Archives of Namibia about a year ago, I discovered a short 1961 article in Die Landbouweekblad—one of the main agricultural publications in southern Africa—describing the visit of Malcolm Allison (an expert on American coyotes) to South Africa. Prominent sheep farmers were invited to test out new control methods and poisons from America, which purportedly would help destroy jackals in the region.

The report fascinated me—Allison’s visit represented an understudied aspect of knowledge and technology transfer, and revealed some of the fervor surrounding “modern” farming. In a recent article, Steven Stoll calls on environmental historians to closely observe not only the form of technology, but its place in broader social relations. The difference between a scythe and a harvester, for example, is less that the harvester cuts wheat at a faster rate, but rather that each represents “different assumptions about the purpose of production.” This post explores how between the 1930s–60s, defensive vermin control practices were “modernized” into offensive vermin extermination strategies. This technological shift was driven by colonial/apartheid desires for a stable white agricultural sector less dependent on local black labor.

In the years after its killing of unlicensed dogs, the colonial administration in Namibia recognized that the number of jackals had increased. As a result, it passed legislation in 1927 creating a network of local “vermin clubs,” made up of 12 or more white farmers who met several times a year to kill vermin: jackals, rooikat, baboons, leopards, etc. Importantly, only white settlers could be members, and all members were granted up to two dogs tax free. The colonial administration also began to pay out valuable bounties for vermin skins. But while in previous years some Namibians, both white and black, had been able to occasionally make a living through vermin destruction, the new legislation formalized and racialized the bounty system in such a way that only white farmers could take advantage of it.

While the vermin clubs did not provide the onslaught against jackals that the state had envisioned, they were the first step toward intensifying predator control: moving vermin destruction away from defensive control measures practiced by individual farmers toward offensive extermination strategies formalized by regional and central institutions. During the 1930s–40s, the Department of Agriculture also started selling strychnine poison at discounted rates to white farmers. Furthermore, the expansion of karakul sheep farming and lambskin pelt production incentivized farming associations to petition for more systematic control measures.

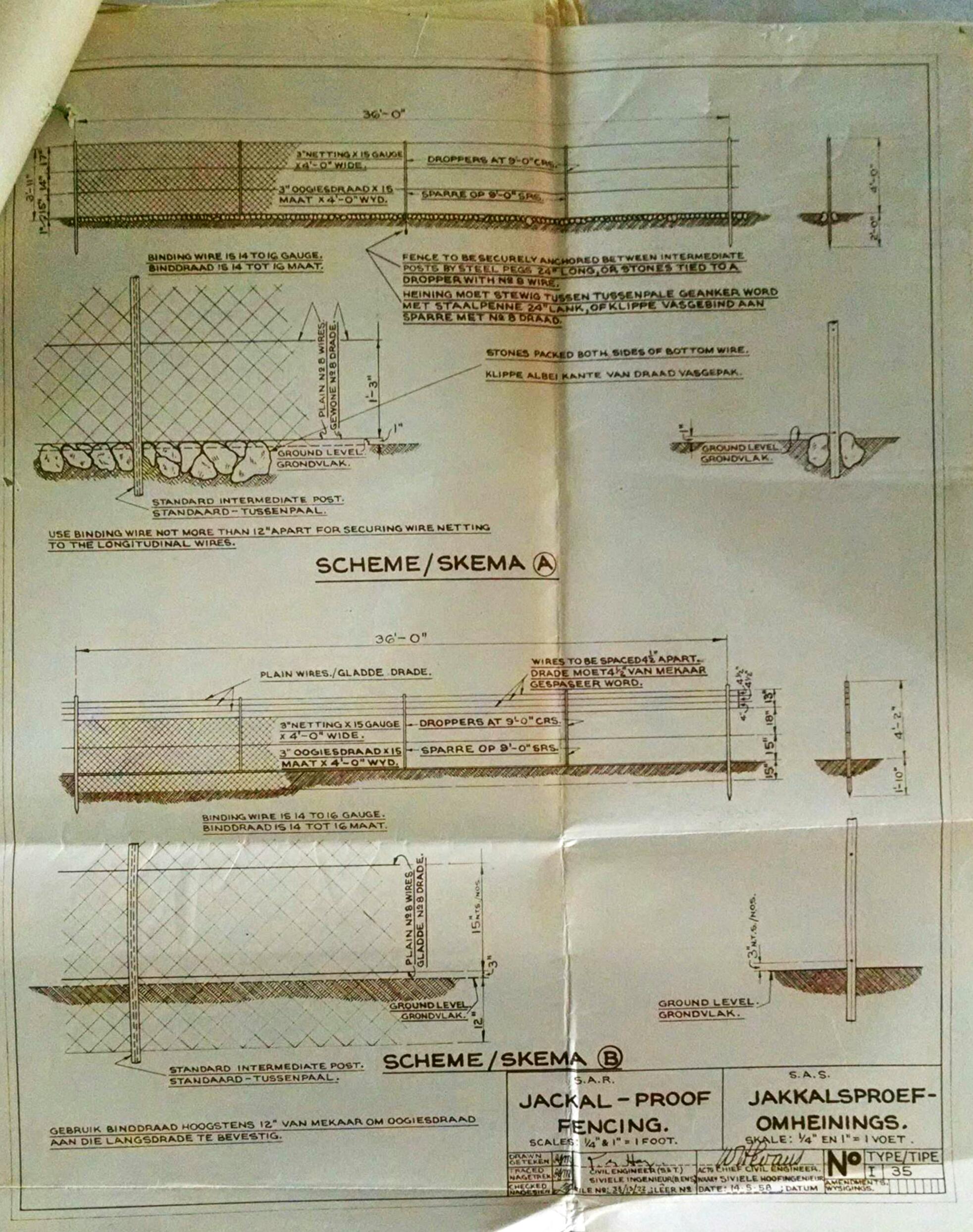

A 1958 schematic for the construction of jackal-proof fencing. (Courtesy of the National Archives of Namibia: SWAA A.486/1/1)

As a result, from 1955–56, the administration investigated new fencing strategies to reduce predation. Inspired by developments occurring in some of the South African Karoo districts, which had through fencing, hunting, and poisoning nearly eliminated the jackal threat, the Department of Agriculture concluded that jackal-proof fencing was key to addressing predation rates (the percentage of a farmer’s livestock lost to carnivores each year) in Namibia, which could be reduced from 1.5–3.5 percent to nearly zero. Crucially, the investigation concluded that nearly half of the shepherding workforce—who were mostly black teenagers or young adults unable to find higher-paying work in the mines—could be made redundant and released. Fredrik Lilja revealed similar trends in his study of jackal-proofing in South Africa: several well-paid shepherds could be replaced with a single low-paid “camp walker,” who tended to fences, rather than sheep.

It was decided that if white farmers elected to register their resident district as a Soil Conservation District (grondbewaringdistrik; hereafter GBD), jackal-proof boundary fencing (tussenheining) between the farms would become mandatory and partially subsidized in cost by the administration. Jackal-proof fencing, as Janie Swanepoel has described regarding more recent periods, was a new kind of spatial predator control. It involved more material than ordinary fencing, making it unaffordable to many farmers prior to apartheid-era subsidies. Large quantities of wire netting were affixed onto existing galvanized-wire fencing, which prevented the jackals from slipping between the horizontal strands. Furthermore, the structure was buried up to six inches below the ground to prevent animals from digging underneath, and it was sometimes built with a veranda to keep the canids from climbing over.

In conjunction with these fencing ordinances and increased enclosure of farms in the GBDs of the south (Karasburg and Keetmanshoop districts), a new policy of offensive vermin eradication was brought in. From 1956, the hunt clubs of the 1920s were reincarnated in new and improved forms. Farm owners were required to construct access gates in their perimeter fencing to allow for vermin clubs to enter their land to hunt jackals. Clubs were permitted to hunt on farms adjacent to the club’s defined territory (gebied), and any jackals killed in this process resulted in a fine levied by the club onto the farm owner; these heavy fines also applied to African communal lands, such as the Bondelswarts Reserve. Over the first few years after the promulgation of the 1956 Vermin Extermination Ordinance, over two-dozen jackal clubs were quickly formed within the GBDs. Within a few years, most of the south was covered by hunt clubs.

By 1964, extermination reached a new level. After the annual congress of the National Wool Growers’ Association (Nasionale Wolkwekersvereniging; NWKV), the Department of Agriculture endorsed its proposal to form District Hunting Associations (Distriksjagverenigings; DJV). All landowners residing in GBDs were now required to be members of the regional DJV and pay an annual membership fee. These funds enabled purchase of vehicles, poisons, weapons, traps, and dogs. Furthermore, the funds were used to hire full-time vermin hunters to lead collaborative commando hunts, or lay traps and poisons on their own.

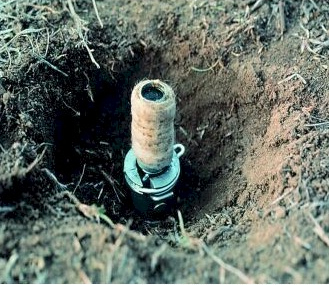

Of critical importance to the success of DJVs in eliminating jackals was the adoption of the US-manufactured “Coyote Getter” (gifskieter). Getters are five- to seven-inch stakes hammered into the ground featuring a powerful spring- or gunpowder-based ejector that fires a cyanide bullet into the mouth of the canid taking the bait. Death is relatively quick, though painful. In 1961, Malcolm Allison and representatives of the US Fish and Wildlife Service offered gifskieter training at South Africa’s Vrolijkheid vermin experimental farm (ongedierte proefplaas). The trials at Vrolijkheid were a success, and farmers found that in combination with other strategies, getters had high kill rates for jackals across all terrains. Gellap-Ost, southern Namibia’s government farm, imported several hundred gifskieters in the 1960s from Colorado, and after successful trials, the administration promptly ordered more gifskieters to be distributed among DJV members who had received training based on the Vrolijkheid courses.

With farms enclosed with jackal-proof fencing and hunting associations armed with the latest poison technology, jackals seemed not to stand a chance. The number of jackals and other carnivores killed in these years was reported to be immense. As noted previously, this was not merely a quantitative change in jackal eradication, but a qualitative one. When offered heavily subsidized training and breeding facilities for jakkalshonde (jackal-hunting dogs) by the NWKV and the South African Vleisraad (meat board), the Department of Agriculture flatly turned them down on grounds that gifskieters and other poisons (like strychnine and Compound-1080) were more effective. This was a qualitative shift; jakkalshonde would have been intended for defensive, targeted killings of problem jackals, rather than toward complete eradication. Gifskieters and gin traps (slagysters), on the other hand, were non-targeted methods of control; they killed young, old, male, female—it did not matter.

Of crucial importance is that eradication strategies were a form of fixed-capital investment intended not only to reduce predation, but also to reduce labor costs. There is evidence of decreasing employment of shepherds on highly capitalized southern farms. A 1958 survey among farmers in Gibeon and Warmbad districts revealed that the mean number of farm workers had decreased to fewer than three. Many of these were contract workers from northern Namibia by this point as well, rather than local Nama labor.

Transformations in agricultural practices and technology in Namibia were, thus, intricately tied to issues regarding political economy and labor. In so doing, narratives such as this—requiring engagement with seemingly mundane documentation and statistics regarding poisons, fencing, and labor costs—blur the line between environmental, social, and economic history. Perhaps Lance van Sittert is correct when he states that environmental history, when it melds “political economy, culture, and ecology” may have “no need of the name.”

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Perspectives Summer Columns Africa Labor History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.