AHA Today , Current Events in Historical Context , From the National History Center

Is Civilian Control of the Military Eroding?

Three of the leading figures in the Trump administration are military men. When President Trump refers to “my generals,” he has Secretary of Defense James Mattis, National Security Advisor H. R. McMaster, and White House Chief of Staff John F. Kelly foremost in mind. By holding powerful positions almost always staffed by civilians, they have provoked widespread concern that civilian control of the military is eroding. As part of its ongoing Congressional Briefing series, the National History Center brought several prominent historians to Capitol Hill to provide perspectives on this subject.

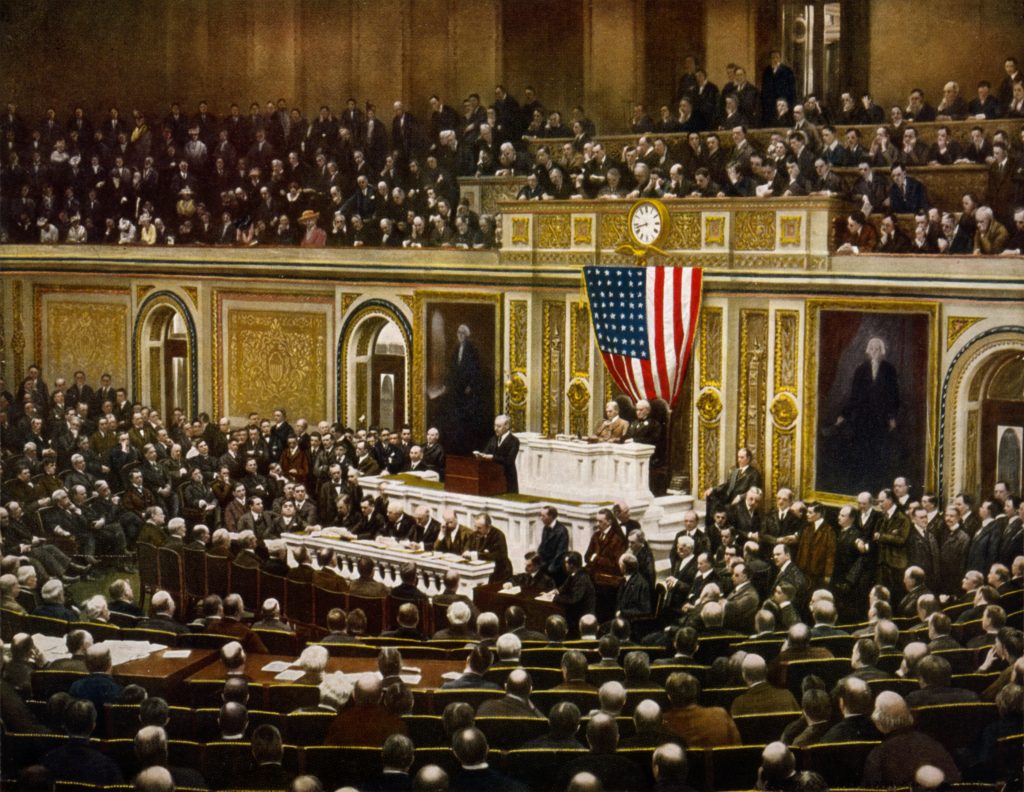

At a recent congressional briefing organized by the National History Center, historians discussed the unusual level of civilian influence over the military in the US, including the oversight authority assigned to Congress in the Constitution. In this print from 1917, President Wilson asks Congress to exercise one of its oversight powers by declaring war on Germany. Wikimedia Commons

Jacqueline Whitt, a military historian at the US Army War College, moderated the briefing and began by asking whether America is undergoing what the journalist Stephen Kinzer in a recent Boston Globe op-ed bluntly termed a “slow-motion military coup.” While the speakers at the briefing did not endorse that view, they raised serious concerns about the current situation. Richard Kohn, professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has written extensively on American military history and civil-military relations. Eliot Cohen, professor of strategic studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, has authored various books on the use of military force and served as counselor of the Department of State from 2007–09.

Kohn began by observing that military subordination to civilian authority was “baked into American political culture.” The Constitution assigned the role of commander-in-chief to the president and gave budgetary and oversight authority to Congress. Cohen noted that this system of civil-military relations is distinctive to the United States. Congress has an unusual degree of oversight of the military, and the dual control over National Guard units by the states and the federal government adds a further layer of civilian influence.

Yet civil-military relations have come under increased stress since World War II and the Cold War, according to Kohn. Especially worrisome are several developments that have taken place in recent decades. One is the growing social and professional gulf between the military and civil society. This can be seen, for example, in the declining number of veterans among CEOs, members of Congress, and other civilian leaders, and in the military’s increasing reliance on recruits from particular parts of the country and families with traditions of service. Another problem is the growing willingness of senior retired officers to endorse presidential candidates, which arguably reached its most partisan expression in General Michael Flynn’s fervid fulminations against Hillary Clinton—“lock her up”—during campaign rallies for Donald Trump.

Cohen cautioned that it is normal for tension to arise in civil-military relations and that political generals have appeared at various points in American history. But he noted that the military is a far more powerful and important institution than it was prior to America’s rise to global dominance, making these tensions more serious. Like Kohn (and Whitt in her introduction to the briefing), Cohen is concerned about the growing separation of the military from civilian elites, noting, for example, that ROTC programs are far less common in our leading universities than they once were. He also worries that the high public esteem currently enjoyed by the military harbors hidden dangers. Maintaining civilian control of the military depends as much on “norms” as laws, and those norms are under assault.

These troubling trends make the generals’ prominent roles in the present administration a particular cause for concern. Kohn worried about the dearth of other agency voices to counterbalance the “troika” of Mattis, McMaster, and Kelly. Generals, he pointed out, are not diplomats or politicians, lacking their knowledge and experience. Although McMaster and the other generals probably see themselves—and are certainly seen by others—as “catastrophe insurance” for an erratic administration, they are trained to follow the orders of their commander-in-chief even if they consider those orders unwise. The irony here is that their commitment to civilian control and the chain of command limits their ability to influence or restrain the president.

Cohen agreed. He feared, for example, that the “troika” is less likely than civilian officials to resist or undermine a lawful directive by the president that they regard as reckless: going to war with North Korea was raised as an example. The only circumstance that might lead them to resign, he suggested, was if their honor was besmirched in the manner of Trump’s humiliation of Jeff Sessions. Cohen also warned of the rise of a “benign junta.” Noting that everyone in government is “the prisoner of their rolodexes,” he worried that Mattis, McMaster, and Kelly are likely to recruit fellow officers to staff junior positions, thereby expanding the military’s influence over the civilian sector.

So what is to be done? Kohn and Cohen agreed that Congress should be more active in asserting its oversight role. Kohn suggested that congressional foreign relations and armed services committees convene hearings on US foreign and national security policy and strategy, filling the vacuum left by a weakened Department of State. Cohen argued that Congress should require that any military officer appointed to a position in the administration retire from active duty. Above all, both of them stressed that it was essential for Congress to reassert the “norms” of civil-military relations.

The National History Center’s Congressional Briefings program aims to provide members of Congress and their staff with the historical background needed to understand the context of current legislative concerns. It does so by bringing leading historians to Capitol Hill to provide nonpartisan briefings on past events and policies that shape the issues facing Congress today.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Tags: AHA Today Current Events in Historical Context From the National History Center Military History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.