AHA Today , Current Events in Historical Context

Memory and Medicine

A Historian’s Perspective on Commemorating J. Marion Sims

Contentious debates over the removal of Confederate general statues that dot our landscape have led the AHA to make an eloquent statement about the meaning of memorialization and history in context. Statues of what in the end are vanquished leaders of a traitorous army, put up during the height of American racism, are a concern, but what about the so-called “Father of American Gynecology” who perfected his techniques on the bodies of enslaved women? The prestigious science magazine Nature waded into this question recently and all hell broke loose.

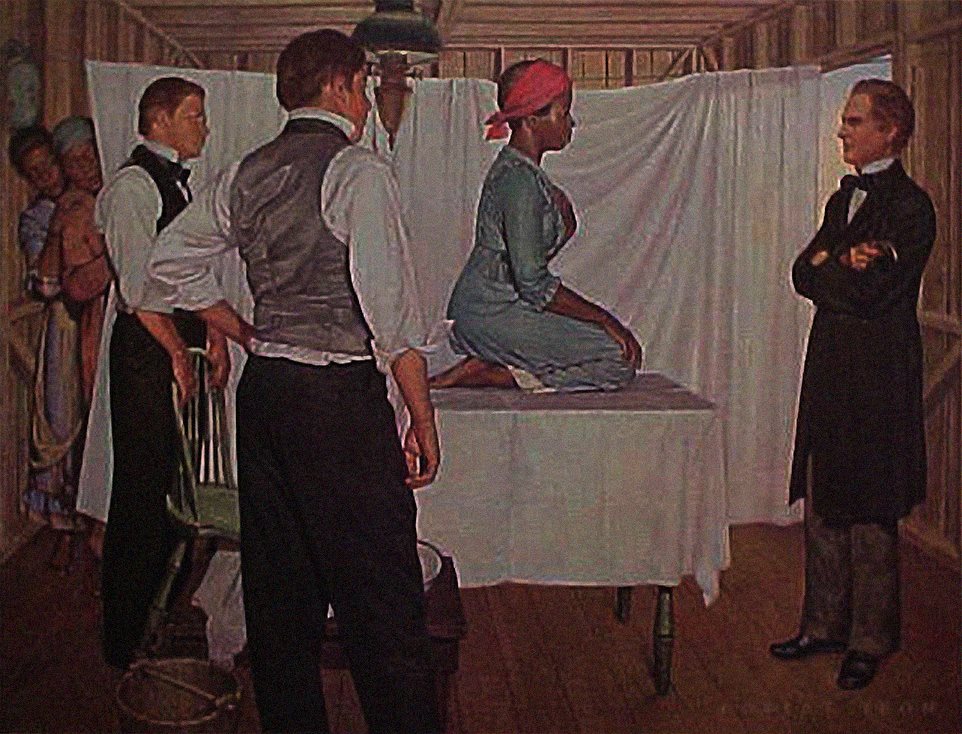

This painting by Robert Thom, part of the Great Moments in Medicine series, is the only known representation of Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey, the three enslaved women Sims operated upon. Fair use

In Central Park, just across from the New York Academy of Medicine in East Harlem, stands a 14-foot marble statue of J. Marion Sims (1813–83). Sims was a gynecologist whose practice mostly centered in a small town outside of Montgomery, Alabama. His claim to fame was the invention of the speculum and his 1840s surgeries on slave women to correct fistulas in their vaginal walls. Fistulas, now seen primarily in parts of Africa, were common in the 19th century. For black enslaved women, fistulas were often a result of rape, repeated pregnancies, poor nutrition, and untreated infections.

Sims moved to New York in 1853, opened a women’s hospital and cancer institution, was president of the American Medical Association, and became an internationally known surgeon who operated on the poor and royalty alike. In his 1889 autobiography, The Story of My Life, Sims tells us that he perfected his fistula sutures on the bodies of three slave women known only as Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey. There exists just one well-known representation of these women in a portrait commissioned by the Parke Davis pharmaceutical company as part of its Great Moments in Medicine series. Vibrant copies of these portraits were sent out by the millions to doctor’s offices across the country between 1948 and 1961. These are the only images of the women we have.

Sims has been controversial for a long time. Even in his day there were questions about his techniques and endless surgeries on these women—whose agony he admitted—to perfect the techniques. Since at least the 1960s, feminist historians, medical ethicists, and community activists have raised an outcry about the adulation of Sims and the ways in which the women upon whom he operated are unknown.

The debate about Sims has been on multiple sides. While he was accused of doing these initial surgeries on black women without anesthesia, he did so in an era when ether was just beginning to be used and it was assumed that women and black people were capable of enduring more pain than white men. The use of black bodies, both alive and dead, alas, was and still is a common medical practice in research.

An East Harlem community group has been trying for years to get the New York statue taken down, arguing this racist symbol should not stand primarily in a community of African American and Latina/o/x New Yorkers. In contrast, other physicians, most notably Lawrence L. Wall of Washington University Medical School, who himself has operated on women with fistulas in contemporary Ethiopia, have argued that Sims’s life-saving surgeries should be applauded and put in their historical context.

In the face of the move to pull down the Confederate general statutes, the organizing against Sims’s tributes has taken on new meaning. On August 19, protesters gathered in front of the New York Sims statute to demand that city remove it. In Columbia, South Carolina, where a bust of Sims has prominence on the statehouse grounds, the mayor is planning on getting it removed. Sims’s likeness still also stands on the lawn of the state capitol in Montgomery, Alabama.

More recently the prestigious science journal Nature waded into the debates with an unsigned editorial insensitively titled, “Removing Statues of Historical Figures Risks Whitewashing History.” An uproar followed with the publication of multiple letters, the invitation for more, and a scathing critique in the Atlantic Daily called “Nature’s Disastrous ‘Whitewashing’ Editorial,” which excoriated Nature for its failure to understand that removing the statue would not be an erasure of history. The critique more or less supported, without citing, the AHA’s position.

Three days later, Nature “corrected” the title to read: “Science Must Acknowledge Its Past Mistakes and Crimes.” This was quite a reversal, and an editorial note went on to admit that the original version was “offensive and poorly worded.” The editors argued, “Our position is that any such memorials that are allowed to stand should be accompanied by context that makes the injustice clear and acknowledges the victims.” This position is not unreasonable, except that it is tone deaf to the ways in which the current debate is happening. Museums serve one purpose, and public monuments another. Museums are the keepers of cultural heritages and can allow for multiple explanations. Public monuments of individuals, in contrast, idealize their lives and accomplishments. Keeping Sims up with just a plaque to the slave women he operated on really does fail to do what seems necessary now as a corrective to the rising violence from white supremacists.

Sims is not the only doctor whose memorialization is being questioned. In 2013 the American Sexually Transmitted Diseases Association voted to change the title of its most prestigious award after much discussion. Originally named for Thomas Parran, the US surgeon general in the 1930s–40s, his support for immoral research studies in both Tuskegee, Alabama, and Guatemala was the reason for the name change. Similar discussions are now going on at the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, where the main hall is named after Parran, the school’s first dean. Historians of medicine have given consideration to these problems and how to think about those we write about in the “court of history.”

Now is the time for Sims to go as well. His statue could be given to the New York Academy of Medicine or to the Brooklyn Greenwood Cemetery where he is buried. A statue to these women should replace him, even if a sculptor would have to imagine their appearances. It is time to stop thinking about the “heroics” of American doctors alone and to consider the people upon whose bodies those exploits were made. A statue of Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey builds new ways to understand the history of medical research and to acknowledge the damage certain practices continue to have as they reverberate over generations. This is how we can contribute to understanding the political function of memorialization and the making of history.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Susan M. Reverby, PhD, is McLean Professor emerita in the History of Ideas and professor emerita of women’s and gender studies at Wellesley College. In 2017–18, she is a fellow at the Charles Warren Center, Harvard University Department of History. She is most recently the author of Examining Tuskegee: The Infamous Syphilis Study and its Legacy. Her exposure of sexually transmitted disease inoculation studies in Guatemala led to a federal apology.

Tags: AHA Today Current Events in Historical Context History of STEM

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.