About a half hour into tagging frontline records in the Operation War Diary project, the room of high school sophomores erupted. “Rats! These trenches are filled with them.” “That’s not so bad; the officer here is talking about trench foot.” “It looks like 95 soldiers died on just this one day!” “My battalion doesn’t seem to move anywhere.” “Oh no! This unit is heading to Ypres.” As an educator, I could not have found the moment more gratifying. My classroom had transformed into a history lab where students were deepening their understanding of the First World War, honing their historical skills, and contributing to an impressive crowdsourcing campaign to make the diaries of British soldiers on the Western Front accessible to scholars, researchers, and the wider public.

Operation War Diary (OWD) was launched in 2014 by the National Archives, the Imperial War Museums, and Zooniverse to mark the centenary of the global conflict.

Operation War Diary (OWD) was launched in 2014 by the National Archives, the Imperial War Museums, and Zooniverse to mark the centenary of the global conflict. The collection contains over one million digitized images of the war diaries of British and Indian troops, offering a fascinating glimpse into the units’ day-to-day activities. Operation War Diary asks public volunteers or “citizen historians” to tag the diaries with a range of variables including dates, places, types of activity, names, and casualties. The records of several divisions are available for annotation, including infantry, cavalry, ambulance, artillery, engineers, machine gun, veterinary, and regional units. The Imperial War Museums harvests the tagged and categorized information to create a permanent digital memorial—Lives of the First World War—telling the life stories of those in the British Commonwealth who contributed to the war.

My goals for getting students involved in the crowdsourcing OWD project were threefold. First, the OWD class project can teach students about the unprecedented and long-lasting physical and psychological trauma wrought by a war often bypassed in US history textbooks. The unit I teach on the First World War is already robust. In addition to textbook readings and lectures, students participate in a role-playing game on the outbreak of the war, discuss war poetry readings, and analyze propaganda. The war diaries add another important dimension by telling the story of this global conflict from the perspective of participants who experienced the industrialized slaughter and its aftershocks firsthand. The project is also designed to develop students’ skills and competencies, such as “historical reading,” chronological thinking, geoliteracy, and others articulated in the AHA’s History Discipline Core. Third, I seek to engage students in the craft of actually doing history, in this case by helping to create data for historical analysis. I direct students to Richard Grayson’s recent study of the frontlines based on data from OWD as a case in point.

The class project (now in its third iteration) consists of two days (2 classes, 80 minutes each) of intensive work with the war diaries. Prior to class, students take a 10-minute tutorial on the OWD site that walks them through the process of accurately capturing places, dates, events, unit activities, and other remarkable historical information. I also provide a brief overview of OWD and guiding questions to focus their attention on life in the frontline trenches, the reality of battle, military technology, and outcomes. A graphic organizer to chart their findings and plan for the final assignment is also supplied. The academic team at OWD has done a marvelous job at creating predetermined categories and user-friendly annotation tools for accuracy. The students are now ready to tag!

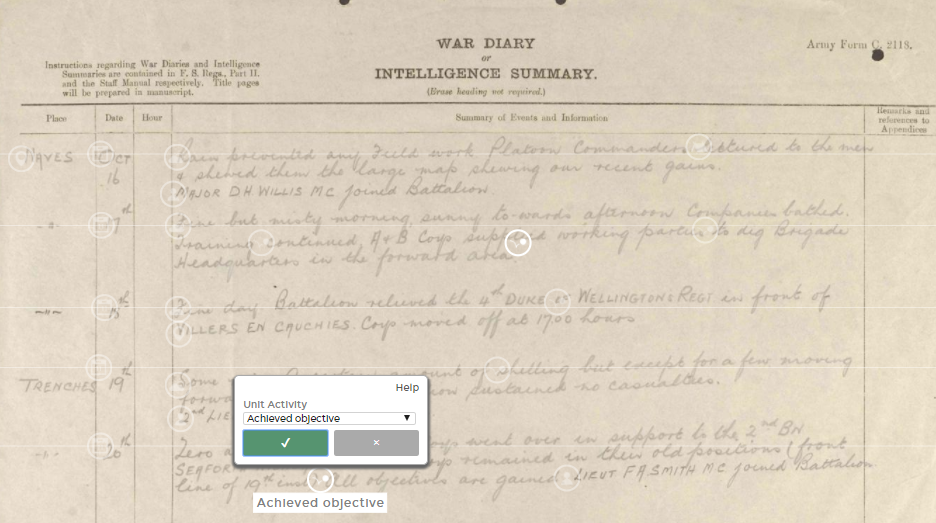

A screen capture of a tagged diary page from the 10th Infantry Brigade, 1st Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment, October 20, 1918. White markers indicate the recorded locations, dates, names, weather conditions, and troop activities. An open tag box shows where a student would note that this unit achieved its set objectives. (Source: Operation War Diary)

During the lively hands-on sessions, I answer individual questions and stop periodically to check for understanding, pose questions, provide background, and fuel discussions on the significance of their findings. Students also make use of a variety of additional resources to aid in the transcription. Operation War Diary offers an easy field guide to help students and volunteers become more familiar with military life and terminology. I have also compiled a list of links such as maps of the Western front, websites on the British Army units in the Great War, and drawings of the elaborate trench systems. In contrast to the usual solitude of archival work, this project engenders a wonderful collaborative spirit as classmates enthusiastically help each other to decipher words—the diaries can be typed or handwritten—or to share stories of the enlisted men in their divisions. Students read portions aloud, compare notes, and assist one another to identify contextual clues in this collaborative learning experience through digital creation.

The summative written assignment requires each student to produce a two-page historically informed reflection on his or her individual work. Their submission must include specific information about the pages of the diary assigned to them: regiment name, dates covered, location(s) for the divisions, and the types of findings encountered in the transcription. Students are then tasked with addressing how the troops’ daily activities support or add to the historical record of the war by connecting their investigations with important themes such as the scale of casualties, life in the trenches, the evolution of the conflict, significant battles, the static nature of the Western Front, nationalism, and modern warfare. They must provide detailed and informed comparisons (or contrasts) with class materials, the recommended online sources, and information from our texts to interpret their findings. The project is also scalable for different educational levels. An undergraduate course could expand and embed this work as part of a long-term project in digital history and historical interpretation of the conflict. Middle school students working in groups could work on a pared-down assignment to learn about daily life on the war’s frontline, the role of primary sources in historical spadework, or to simply connect to the past with digital technology.

The idiosyncratic and richly detailed nature of war diaries produces unique and nuanced student reflections. The adjutant authors of the records had few formal guidelines; consequently, the pages vary in terms of topic, information, and tone. While students may expect to read about the new weaponry such as poison gas, they are surprised and intrigued to learn about rationing, hygiene, recreational activities, and village life near the frontline that gives a fuller picture of the social dimension of war. Their reflections often remark on how seemingly dry official reports sometimes provide overbearingly moving testimonies of despair, cynicism, courage, terror, and even hope. In one exemplary reflection, a student analyzed how George V’s visit to her battalion in 1916 not only boosted soldier morale on the ground, but also contributed to the continued consent and support of the home front for the war.

The Operation War Diary project has proven to be powerful student-centered learning experience with digital history. Some scholars may bristle at the claim that crowdsourcing itself transforms students into “citizen historians.” Yet, this activity and accompanying assignment has successfully served not only to strengthen their historical skills, but also to stimulate curiosity and appreciation for the discipline, which may inspire students to pursue history later in life. Feedback on the project has been overwhelmingly positive. Students’ reflections show that they enjoy their roles as sleuths and budding historians. Above all, the diaries never fail to have a profound impact on them. As one junior stated, “When reading or listening to facts about the war, I was never able to see what it was like on a personal level for young soldiers. The diaries made it so I could understand that the war was their life.” Operation War Diary offers a unique opportunity to take students beyond the school walls and into the trenches of the Western Front, not to humanize war, but to reveal the human experience of the global conflict that shaped the 20th century.

Sample Assignment and Graphic Organizer

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Susan Corbesero, PhD, is history department chair at The Ellis School in Pittsburgh and teaches seminars in modern European history. Her research and teaching interests include Soviet/Russian history, gender studies, visual culture, and digital humanities. Susan is also the co-creator of Stalinka: A Digital Library of Staliniana at the University of Pittsburgh.

Tags: AHA Today Military History K-16 Education Teaching with Digital History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.