“Never underestimate the ‘hangry.’” This might as well be one of the learning objectives in my Foundations of Western Civilization course at Utah State University. Whether the bread riots of the 1790s in France, the “Hungry 1840s,” or the starvation of Russian citizens after the conclusion of World War II, food (and access to it) has continued to be a mobilizing factor in history. By examining what people ate and how they ate at different points in time, we can know a lot about a particular era’s economic conditions, social mores, political conflicts, religious issues, and nutrition. For the past three semesters, my students have used Northwestern University Knight Lab’s TimelineJS to create a digital chronology of the history of food in Western civilizations from roughly 1700 to 2001. Using food as a lens to examine the history of the modern West with a digital timeline is an illuminating and engaging method to teach a general education survey.

A screenshot from students’ collaborative chronology, created using TimelineJS, on food in the history of modern Western civilization.

The food timeline served as the main research component of my survey-level course. The digital history assignment encouraged students to develop the same skills they would with a traditional research paper. For example, using the university library’s resources and the web, students found and analyzed primary as well as secondary sources. They also identified and explicated historical significance with an eye to historical causation. In addition, with this project, they tuned their digital skills using TimelineJS and developed media literacy skills in the process.

For the assignment, students worked independently or in groups (of no more than four students each) to research and write entries for the timeline. Each group or individual was responsible for three entries over the course of the semester. To ensure that we considered the entire period from 1700 to 2001, groups had to write one entry for each of these distinct periods: the Enlightenment to the first Industrial Revolution; the first Industrial Revolution to 1914/the start of World War I; World War I to 2001.

Entries were two to three paragraphs in length (300–350 words) and could discuss crops, meat, processed foods, recipes, utensils, rations, agricultural innovations, events related to food, or manufactured products from Europe. The entries had to be both descriptive and analytical. Students were required to explain how their entry represented the larger historical trends at the time, either socially, economically, and/or politically. Each entry also had to draw on at least two primary or secondary sources, one of which had to be a printed, peer-reviewed source such as a historical monograph, scholarly article, or even a scientific research paper.

We spent a good deal of in-class time discussing reliable and unreliable sources, especially on the web. At the start of the semester, students also attended a mandatory “library instruction day.” During this class session, they were introduced to TimelineJS, Google Sheets, Google Docs, Google Hangouts, and the library’s online and physical resources. For many of my students, this was the first time they had been in the library let alone been able to harness the power of the library’s online databases and large physical holdings (including vintage Jell-O molds!). To further aid students with evaluating sources, I had them use a source evaluation worksheet.

TimelineJS is an easy-to-use resource for instructors who want to implement a digital component into their course. Knight Lab provides detailed instructions and a Google Sheet template. All instructors have to do is download the template to a publicly available Google Sheet, publish the sheet to the web, and then share the link with students who will need to input the information. Knight Lab does the rest, with the text automatically uploading to the visual timeline. Although it does take some checking and fixing on the instructor’s part, the process is not time consuming or difficult. TimelineJS can be used in a variety of courses, from high school history courses that want to prioritize chronology; college-level survey courses that want to emphasize change over time; and even advanced graduate courses where the class works on a digital project together.

In my survey course, once students had completed the research and written their entries, they were able to upload the information to our class’s Google Sheet. Detailed instructions along with two in-class demonstrations helped students understand how to input information into Google Sheets. Although this seems like a small learning outcome, students can transfer these skill to other classes and, eventually, to their careers. What resulted from these entries was a visually stunning, collaborative timeline of the history of food in modern Western civilization.

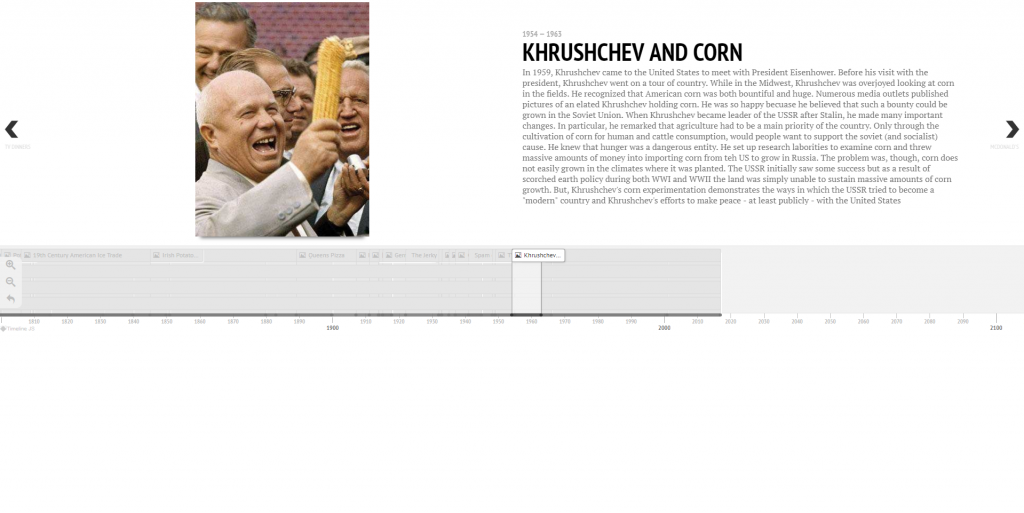

I brought this timeline into class as much as possible, drawing attention to the students’ work when it was relevant. This was a way to not only recognize students’ hard work, but also to further demonstrate how food reflected larger historical issues and events. For example, when we discussed the post-Stalin decade of the Soviet Union, we pulled up the timeline to examine a group’s entry on “Khrushchev and Corn.” The group’s image, a cover of Life magazine, shows an elated Khrushchev visiting a US farm, holding a huge ear of corn. The other students in the class were immediately intrigued by the funny image. The group explained that the photo was taken during Khrushchev’s visit to the United States in 1959. Khrushchev was astounded by the size and abundance of corn in the Midwest. The students told us how Khrushchev was in the process of trying to build the Soviet Union’s corn supply as a way to feed people and livestock. We discussed how Khrushchev’s corn experiments were indicative of a shift in Soviet priorities in the post-Stalin era, a clear example of scientific experiments, and a gradual thawing of the Cold War. Bringing the timeline into the classroom advanced in-class discussions.

For many of my students, this project truly engaged them in the study of history through a lens that was previously unfamiliar to them. A student commented on an end-of-semester evaluation that the project helped them see the many deleterious effects and impacts of war on civilian populations, something they missed by only studying conflict through a political lens. The timeline project also helped another student take an introspective look at the sustainability of certain food processes in the present era. Getting students to think historically and critically about something as commonplace as food was a very rewarding aspect of this project. The food timeline will continue to be a cornerstone of my Western civilization course as it provides historical, analytical, and digital skills to survey-level students.

Food in the West: A Timeline, 1700–2001

Instruction Packet

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Julia M. Gossard is assistant professor of history and a distinguished assistant professor of honor’s education at Utah State University. She teaches undergraduate and graduate-level courses on the history of early modern and modern Europe. A historian of 18th-century France, Julia is finishing her manuscript, Coercing Children, that examines children as important actors in social reform, state-building, and imperial projects across the early modern French world. She is active on Twitter. To learn more about her teaching, research, and experience in digital humanities, visit her website. She wishes to thank Utah State University’s Merrill-Cazier Library’s interdisciplinary assignment charrette workshop and the American Historical Association’s assignment charrette workshop at the 2017 annual meeting in Denver. Each workshop helped her refine the instructions, organization, and learning objectives of this assignment.

Tags: AHA Today Food and Foodways Teaching with Digital History

Comment

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.